The Top Albums of 2016

The best music from 2016 meant more than usual this year

As I began writing this, I accidentally deleted my entire Spotify library.

Every year, when I begin compiling my favorite albums from the previous 12 months, I clear my library of anything from previous years. But this time, I selected the wrong batch—and inadvertently removed everything I’d saved from 2016. A simple user error. A slip of the keyboard. And every bit of the material I needed to write this column.

My first reaction: There’s no need to panic. Surely I could work my way out of this mess. But it didn’t take long to find out that Spotify can only reinstate lost playlists—once deleted, any songs or albums stored in your library are irretrievable and have to be added back manually, one by one.

My next reaction: Ask for a deadline extension.

OK, I thought, I’ll rebuild my library. Maybe just the stuff I recalled quickly, as whatever was the most memorable would, I figured, be the most worthwhile. But what would I inevitably leave out? For the purposes of my list, it matters. I intend these articles to be a complete list of the music I liked most in any given year. Not wanting to leave out anything I enjoyed is why, a few years ago, I dropped the pretense of a “top 10,” choosing to let the music determine the outcome, whether it was 19 albums in 2013, 31 in 2014, or 75 in 2015.

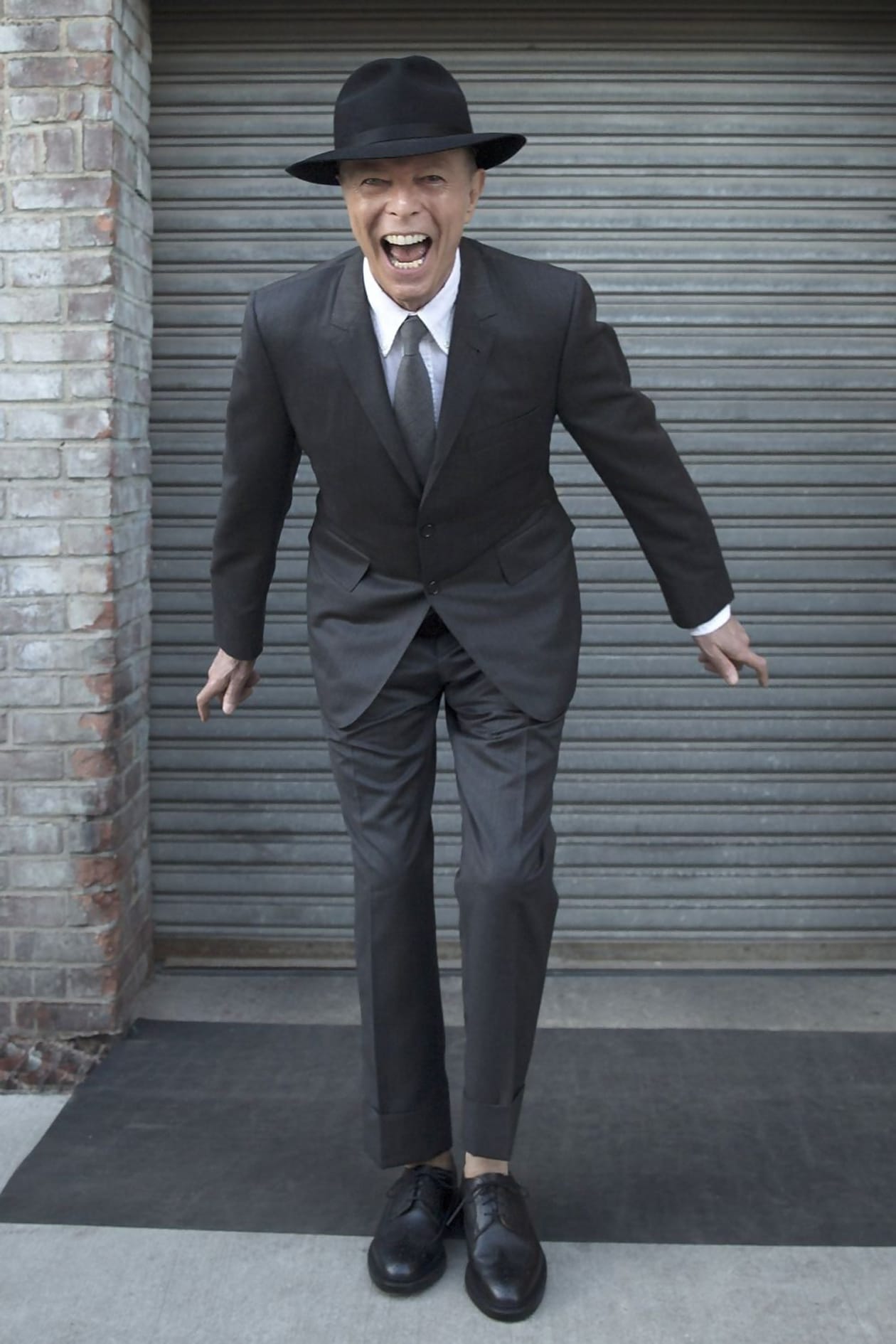

That last column, from a year ago, wasn’t only about the music I liked, but why I liked certain music. As I realized then, I can trace almost all of it to David Bowie. Not music that sounds similar to his output, but how his influence on my taste opened doors to new and different music. Ten days after that column ran, he died. As it did for millions of other fans, his death cast a shadow over my 2016.

But that was then, this is now, and the countdown is on. With no catalog to access, no notes saved, how did I write this year’s column? I stopped. I stopped attempting to undo what couldn’t be reversed. I stopped and realized my only choice was to move forward, to throw myself into the outcome. To take a page from Bowie: I had been thrown an Oblique Strategy.

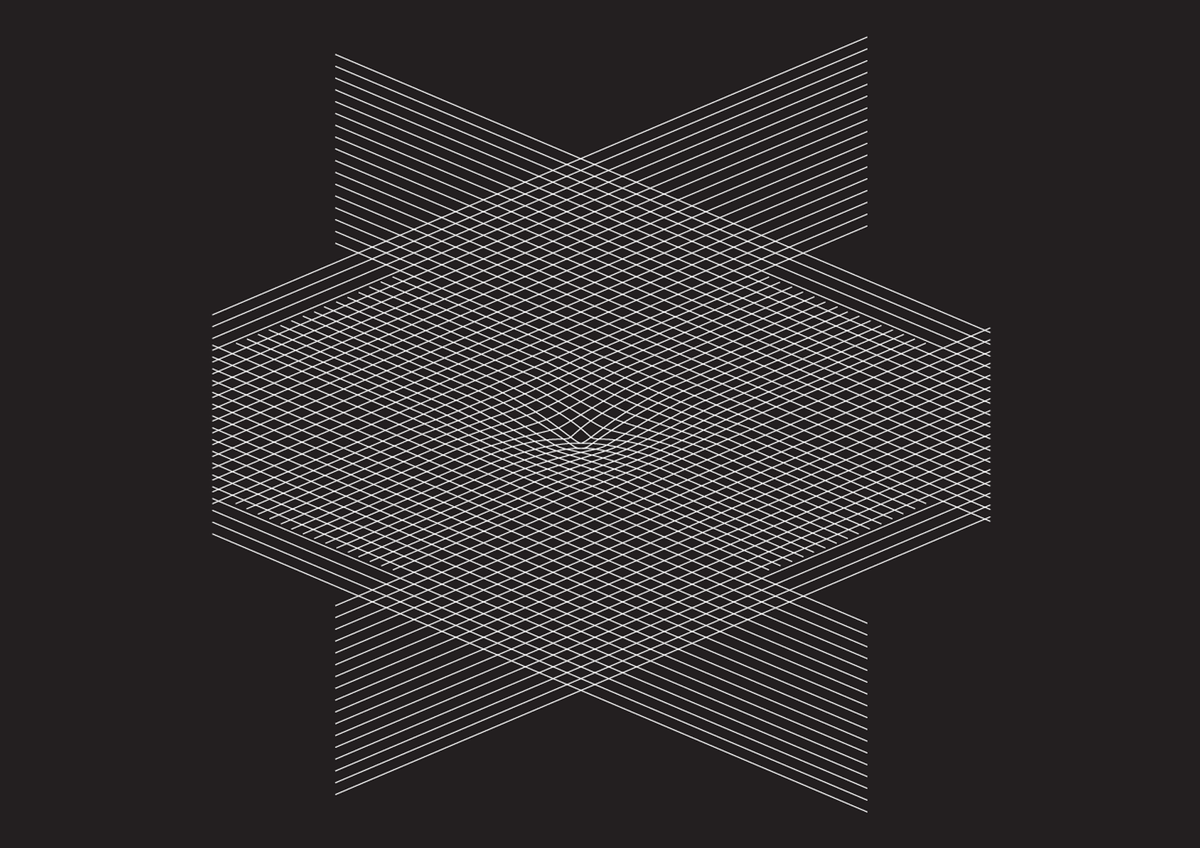

Created by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt in 1975, Oblique Strategies are a deck of cards, each with a single, sometimes vague statement that, depending on how the individual interprets it, can spark a creative solution for navigating past a creative block. Shuffle the deck, draw a card, let it inspire your next move. Most famously, Eno used the cards with Bowie during the writing and recording of their Berlin collaborations (Low, “Heroes,” Lodger). Examples of Oblique Strategies include “Tidy up” (a favorite), “Do nothing for as long as possible” (I would but the clock’s running), and, especially relevant:

Make a sudden, destructive unpredictable action; incorporate.

I reopened Spotify and looked at the space where my library once lived. I looked at that emptiness and began to see more than what wasn’t there. I found I was staring at an outcome I hadn’t anticipated. I was looking at the void.

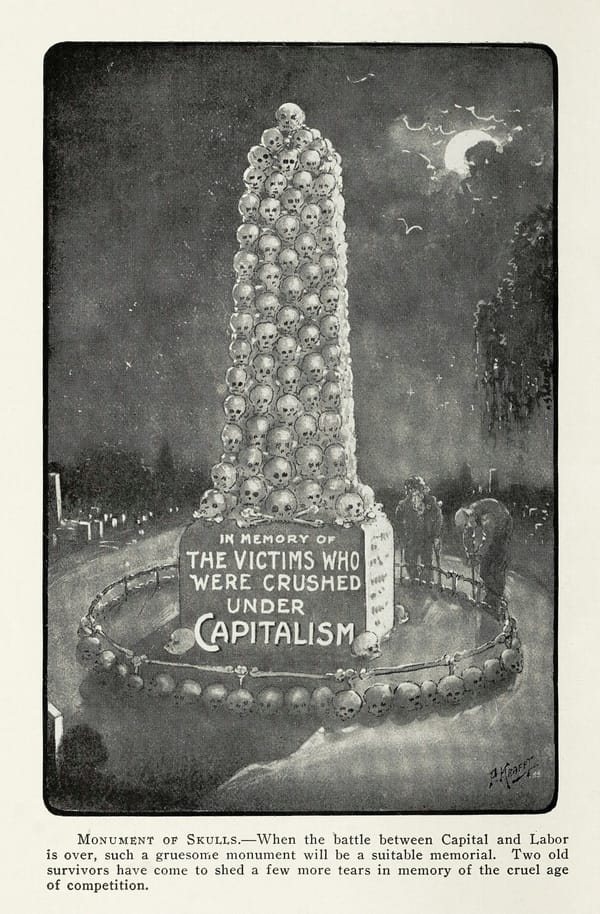

The void is the unknown. For all of us, that void is always one step away, one step into the future. But so many of us do a superhuman job of keeping it filled with other things. We load up the void with entertainment, with the things we know to avoid the unknown. We make plans, we observe rituals and traditions, we wake each day with the goal of making the future knowable, dampening the vast uncertainty. We fill our lives with the things that matter: our families, our careers, our advancements. In yoga and meditation, we employ a drishti, an intense gaze to block all other distractions. We strive to be here now, and to ignore the void.

Rather than ignoring it, step inside.

Theo: A hundred years from now there won’t be one sad fuck to look at any of this. What keeps you going?

Nigel: You know what it is, Theo? I just don’t think about it.

For me, listening to new, unfamiliar music is to enter the unknown, however briefly. I don’t yet understand what I’m hearing, don’t know what to anticipate, and—because I’m lost—immediately try to find my way by looking for signposts. What other songs or artists does this remind me of? What genres am I hearing? I fill the unknown with what I know, comforting myself against unfamiliar territory. I suspect we all do this.

Music services, stores, and critics alike eliminate your fear of entering the unknown by categorizing music along the rubric of “recommended if you like.” If you like that artist, you’ll like this album by another artist, and doesn’t it make you feel better to know ahead of time what you’re getting into? When Spotify first introduced its “Discover Weekly” playlist, designed to introduce users to music personalized to their tastes, users reported a bug: The algorithm was inserting songs they’d already heard. But when the bug was fixed and only new songs were played, user interest dropped. The bug was reinstated, and the playlist’s popularity took off.

How much of the unknown each of us can accept is up to our individual tastes. When hearing an unfamiliar song, if I’m able to fill it up right to the top with other references then I’ll regard it as simply derivative. There’s a ratio of known versus unknown I want in new music—it’s why the music I end up cherishing the most I initially dislike, my brain rejecting it the first few times I hear it. The fewer navigation techniques I have, the less I’m hooked in, and need time to adjust. Only then can I appreciate the music in and of itself, and it becomes its own reference point to which I’ll compare other music.

I want to be a brave listener, but getting there means discarding the comforts of familiarity.

Eighteen months before the release of ★, his final album, David Bowie was diagnosed with cancer. Whatever real or imagined meanings the songs might hold for us as listeners, over the course of that year and a half, he wrote and recorded much of the album with the knowledge that he didn’t know what would happen, that the future was in question. This album is a chronicle of an artist gazing into the unknown. As a listener, this is an opportunity to observe that through his eyes. To step even deeper into that nothingness.

We could fall on lazy habits and analyze it in sedate terms: Doesn’t this part sound like a cross between Diamond Dogs and Aladdin Sane? Does this song recapture the unabashed experimentalism of Low? Is the album reminiscent of Station to Station’s unhinged soul?

While it’s soothing to look backward, it’s precisely not where Bowie is heading. He’s looking forward, at what’s ahead of him—and directing us to look at it as well. We can be unafraid of the future, of what we don’t comprehend, and we can live freer, further within the void, accepting just how little we know.

This has been a long year, with an even longer election. The future is always in doubt, but rarely has a new year felt so uncertain. We have so many questions, and so few answers about what to expect.

Our deadline is fast approaching. We know by now there will be no renegotiation.

It’s our collective future and we’ll live there, but we must decide how. Clutching to the past, overcome by fear? In the present, relying on an alternate set of facts, avoiding reality? Or:

With confidence, sizing up the unknown, no longer denying its presence, and living bravely in the face of it.

Album of the Year

David Bowie, ★

Originally published at The Morning News