The Top Albums of 2018

Following a mid-year checkpoint, catching up on the rest of 2018 with picks from the year in music

The albums below cover the second half of 2018. You can see album picks for the first half of the year here: The Top Albums of 2018 (So Far).

I have never loved deadlines more.

I tried something new in how I listened to music this year. Rather than squeezing 12 months into one collection, as I usually do, this year I stopped myself around the midpoint of 2018, and posted my favorite albums of the year (so far). The result was that I ended up listening to a mostly different set of albums in the second half of the year, and—in terms of listening habits, anyway—that change made the first half of 2018 and the second half feel (or at least sound) like two distinct years to me.

Taking another step back, in bisecting my year with an unnecessary deadline, it made 2018 feel much longer than a typical year. I wonder if inserting more deadlines, separating more periods of time like this could in effect slow down my perception of time’s passage, reducing the blur between days and weeks, and creating more unique, personally meaningful spans of time. For me, it’s done with this process of listening to and thinking about music. For you, it might be something else.

For those who still define a “year” as “12 months,” then here are my album picks for the first half. Below you’ll find my picks for the second half of “2018.”

Here’s a Spotify playlist of my 55 favorite albums from the second half and a full, 93.5-hour playlist of all my album picks for 2018. And here are song picks—one from each album—for the second half as well as the entire year:

Best wishes for a happy—and expansive—2019. Thanks for listening.

Amnesia Scanner, Another Life

Each track is carefully collaged and deconstructed with simple melodic synths and morphed saw-bending, glitch sounds that make you feel uncomfortable yet also are made to make you dance chaotically. I would describe it as post-EDM/industrial club music with some grime and witch house influences. Anyway, this album fucking bangs. Play it loud. (KVRX)

Anderson .Paak, Oxnard

But the story of Oxnard—and Malibu and Venice, the other two pieces in the loosely connected “beach trilogy” that the new album closes out—is that Anderson .Paak is both a formidable talent and a work in progress. Oxnard exhibits growth in its sonic architecture, especially in the carefully tailored rhymes, sweeping vocal harmonies, and wigged-out instrumental passages that give these songs, and the album by extension, the exhilarating unpredictability of a trip along a winding superhighway. (Vulture)

Anna Meredith, Anno

Even when Meredith brings in harsher techno elements they fit alongside the Italian composer’s work like a glove. “Stoop” climaxes with a pounding cataclysm of sound, while “Low Light” combines harpsichord and strings with a glitch-ridden foundation of beats that flows into the dramatic, high-tempo first segment of Vivaldi’s “Winter” perfectly. ANNO stands as a collection that casts an old master in a new light while cementing Meredith’s place as a constantly startling and boundary-breaking contemporary composer. (The Skinny)

Arp, ZEBRA

The album’s primary mode is a kind of airy, bright art pop in which marimba melodies ripple across a turquoise expanse of Mellotron, and fretless electric bass and acoustic guitar drip like moisture down a just-finished glass of Campari. It’s possible to detect hints of Talk Talk’s ethereal psychedelia in the playful weave of woodwinds, electronics, and earthy hand percussion. (Pitchfork)

audiobooks, Now! (in a minute)

On the whole, Now! (In a Minute) is wildly entertaining. From delightfully wonky dancefloor fillers to tangled electronics, Wrench’s seasoned production skills pay off again and again. Audiobooks also manage to play (and it does feel like play) with deeply human themes like coming of age, familial dysfunction and young love without ever losing their undeniable mystique. (The Line of Best Fit)

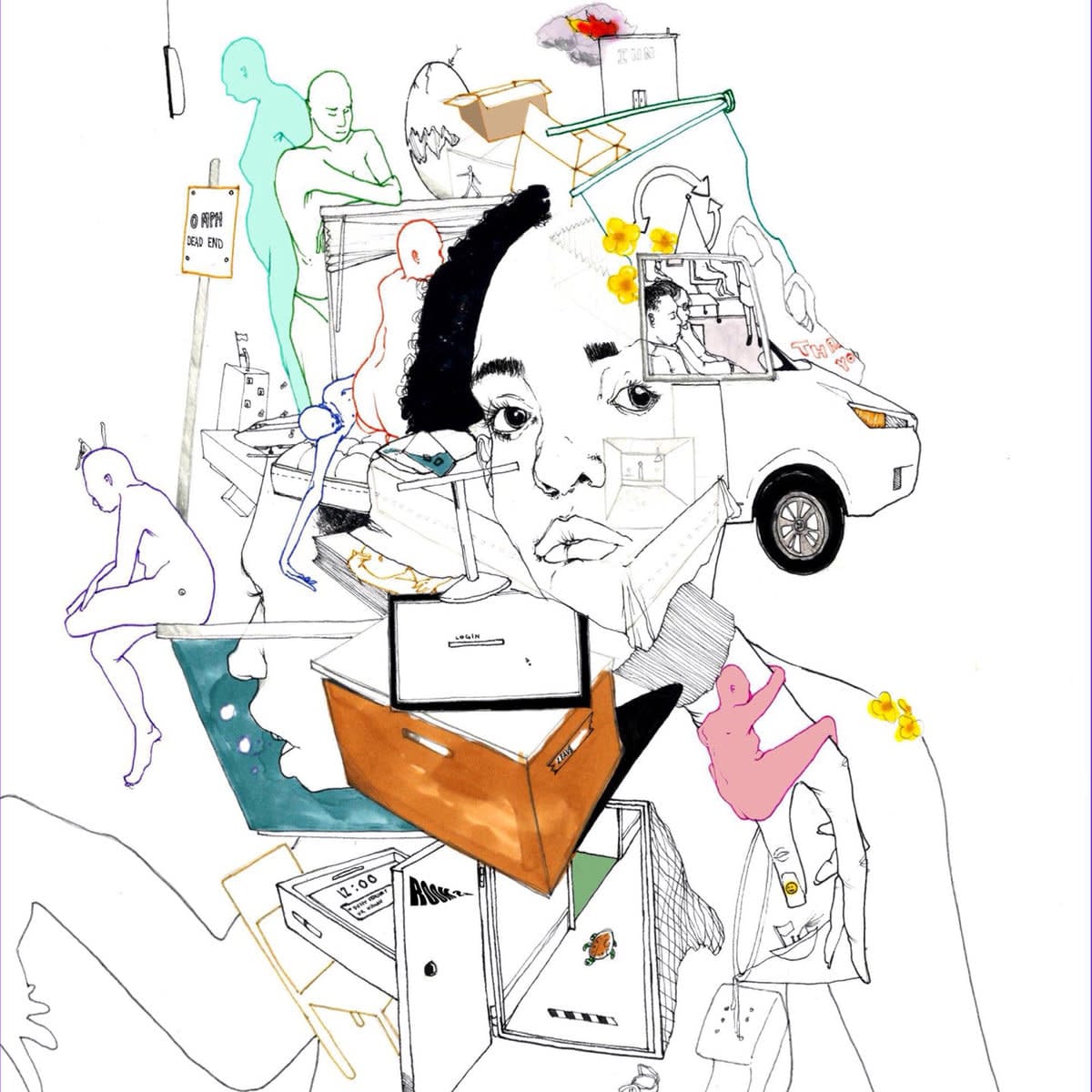

Blood Orange, Negro Swan

Negro Swan’s world-weary opening track “Orlando” offers a 21st-century update on those tragic politics of deflation and depletion. Hynes’ production goes for pretty, sprightly textures: sampled street sounds, twinkling electric piano, chicken-cluck wah-wah guitar, and a mid-tempo funky shuffle beat. As if to alert us to sudden danger, a dancehall-style alarm goes off (alarms are a recurring motif on the album). Sounding like a quivering Curtis Mayfield, Hynes falsetto-croons the hook, “First kiss was the floor,” a blood-chilling reflection about being bullied/bashed as a child on a school bus. (Pitchfork)

Chilly Gonzales, Solo Piano III

His style is metrical and precise, his fingering dainty. When Gonzales “bends” notes, he doesn’t use the slurring technique of a blues pianist, but instead plays crisp, chromatic runs. His compositions are filled with elegant misdirection, gentle dissonance and musical in-jokes. “Prelude in C Sharp Major” twists the arpeggio from Bach’s C major prelude and recasts it in a disorientating 5/4 time signature. “Present Tense,” a fast and dramatic fugue in 7/8 time, is dedicated to Thomas Bangalter of Daft Punk, and as the piece develops you realize he’s playing the riff from Daft Punk’s Around the World but hiding it in a Bach-like contrary motion pattern. (The Guardian)

Chris Liebing, Burn Slow

For those that find beauty in the darkness, there is much here to enjoy. The individual cuts have an edge and a kinetic flow as if we are on a dangerous chase that never ends. But it is clearly not butterflies we are after. And if there are apparitions, they are not the friendly kind despite their gossamer appearances. There is something sinister about the “Ghosts of Tomorrow” even if we don’t understand what the spirits represent. (PopMatters)

Cloud Nothings, Last Building Burning

The band have never sounded as in sync; the years of playing together as a cohesive unit have paid off. A ferocious album that finds them diving headfirst into experimentation, it is filled to the brim with a driving energy that rarely lets up. Striking the precarious balance of melding their pop inclinations with uproarious noise, Cloud Nothings push the dial back in the right direction. (Consequence of Sound)

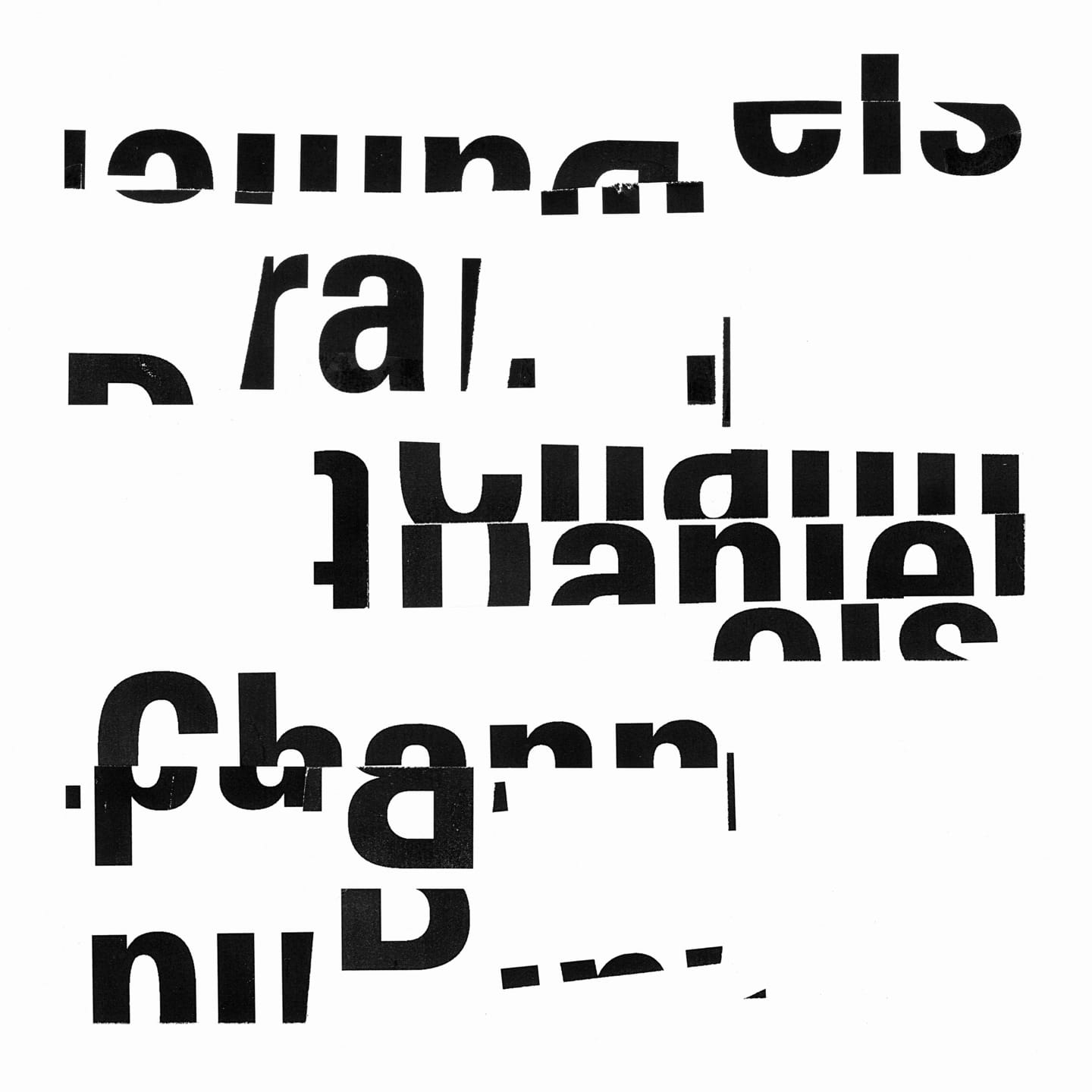

Daniel Brandt, Channels

The formidable, but never domineering bass in “Sailboats III” enables the track to stray successfully into both club and krautrock territories, without ever getting lost in either. And it’s this sense of discipline underlying the (acknowledged) use of influences such as Tangerine Dream and Steve Reich that contributes to a record that might have been, ultimately, considerably less than the sum of its constituent parts but which is in fact consistently engaging and never complacent or over-indulgent. (The Line of Best Fit)

David Allred, The Transition

Such a minimal approach in the wrong hands (and voice) can often become tedious, but Allred has an excellent singing voice and serious instrumental skills to carry this concept through. This musical approach is also something that fully complements Allred’s lyrical concept presented on “The Transition,” inspired by his daily work in a residential care home. Not your cheerful entertainment theme, but with his musical and vocal capabilities, Allred is able to give it the poignancy he seems to have intended to devote it. Often, as on the title track and on “The Garden”, the effect Allred creates is quite mesmerizing. (Soundblab)

Dedekind Cut, Tahoe

For his debut on the esteemed Kranky label, Tahoe finds the Sacramento native not only returning to the West Coast but also fully pivoting to ambient music. While a noir twang ran through his recent mixtape as Barrio Sur, Tahoe wholly embraces the conventions of the genre. Opening tracks “Equity” and “The Crossing Guard” are so hushed that, if heard as the soundtrack for your morning commute, they dissolve almost completely into the daily noise. Quieter surroundings are required to really hear Bannon in motion. (Pitchfork)

Earl Sweatshirt, Some Rap Songs

Amusing dismissals of his rivals are frequent, whether it’s in beautiful longform poetry on “Loosie,” or in neat punchlines: “They stable full of sheep, we staying on the lam”, “I heard you got your sauce at the Enterprise”. There is frequent reconciliation with his parents (after the frictions that had a teenage Earl sent to school in Samoa), most movingly on a track that weaves together public speeches by the pair of them. And there is evident joy in the sly pop catchiness of the tight triplet flow on “Nowhere2go” or the chorus of “The Mint”—moments like these put Earl in a lineage of truly great MCs from Nas to Cardi B, who can turn a melody out of an idle utterance. (The Guardian)

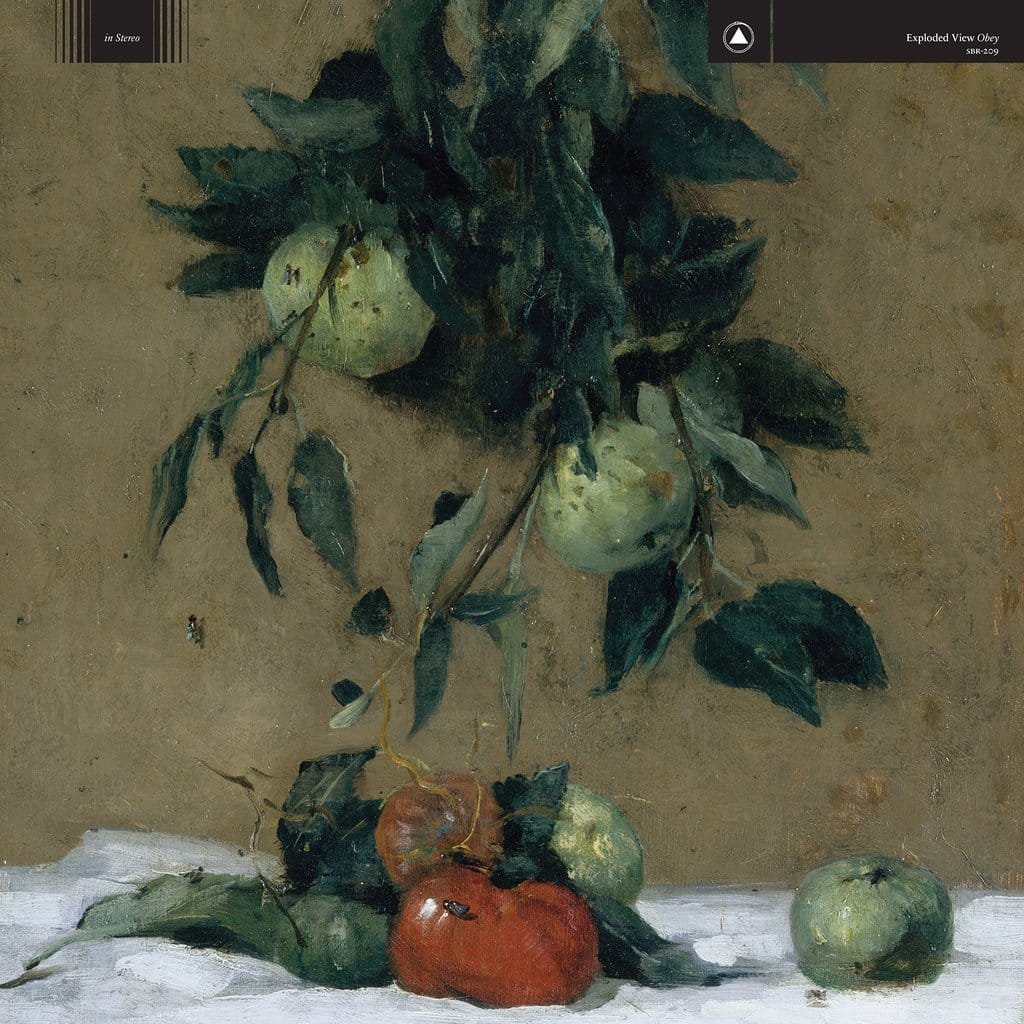

Exploded View, Obey

In a surreal manner, the opening track and its pensive characteristic give way to “Open Road”, which arrives with a psychedelic twist. The hallucinatory element of the track with its brilliant, bubbly background fuses with the bizarre instrumentation and the hypnotic progression for an intoxicating result. The dark folk tone of the track is undeniable, and it is an element that the band further explores on the title track. With the main theme mirroring a middle eastern melody, the folk characteristic meets with the psychedelic touch for an otherworldly result. (PopMatters)

Felicia Atkinson, Jefre Cantu-Ledesma, Limpid as the Solitudes

The four compositions on Limpid as the Solitudes reveal few clues as to how they were made. There’s a sort of alchemy at work in the way the two create a pool of noise and echo in which sounds bob like buoys in a wine-dark sea. On the opener, “And the Flowers Have Time for Me,” they introduce countless little details across a nearly six-minute span, creating a fully realized world to inhabit: what might be a crowd jostling in public transit, the pulse of an EKG machine, naked flesh rubbing up against coarse fabric, doors opening and closing, water pouring from a carafe, birds chirping, storms cloud gathering on a sunny day. (Pitchfork)

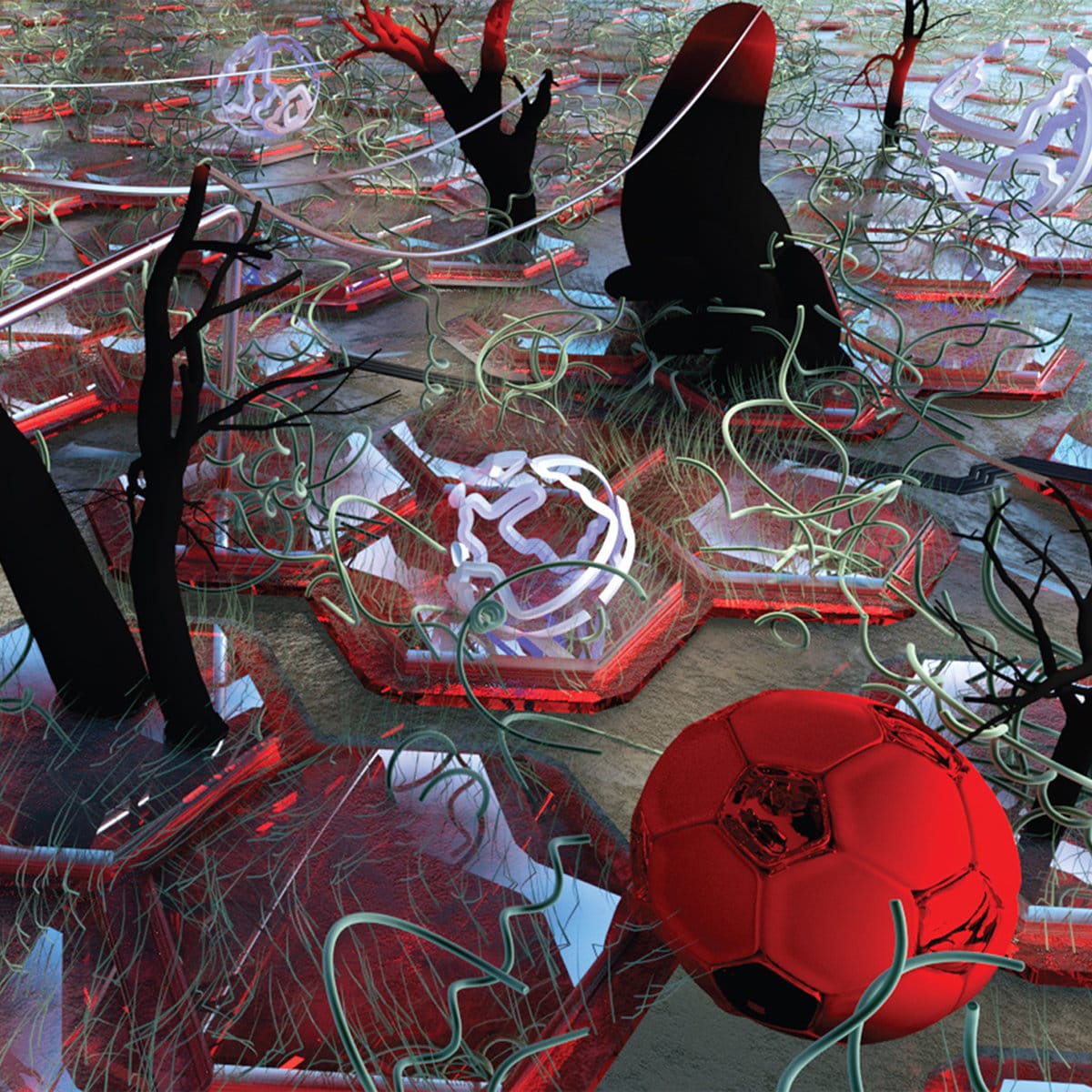

Fire-Toolz, Skinless X-1

But what that means, as Skinless X-1 demonstrates, can be a pretty wild thing indeed. Each track follows a strange, jumpy logic, fractured and fragmented in the way your memories of your dreams might be. “✓ iNTERBEiNG,” to give just one example, moves from night-drive guitar arpeggios into unpredictable glitchy ambience, befitting some of the slower Autechre tracks, before rocketing back off into a giddy synth riff and spidery riffing that kinda feels like Joe Satriani surfing over a nightcore remix of an Envy track. (Noisey)

Haley Heynderickx, I Need to Start a Garden

I Need to Start a Garden carves paths through loneliness and confesses long-harbored uncertainty, doing both with the acuity of someone comfortable enough to be honest about her doubts. Though the album is supported by a number of other musicians, Heynderickx’s craft feels solitary. In many passages, she accompanies herself on just acoustic or electric guitar, using a fingerpicking technique adapted from the style she practiced as a kid taking lessons from a local bluegrass player. (Pitchfork)

Helena Hauff, Qualm

With Qualm, Helena Hauff has created the record we both wanted and needed. It’s a statement of romantic infatuation amongst an otherwise hash, twisted and raw landscape. A glance into the past and a look to the future. There is nothing apologetic about this record, and that’s what makes it so great. (Clash)

Ian William Craig, Thresholder

The combination of the purity of the vocal tone and the degrees of roughness of the framing (between a minimal granular abrasiveness and a sound that resembles nothing so much as a catastrophically damaged 78 beyond all hope of salvation) encourages one to listen with close attentiveness to appreciate the range of sound textures. Comparisons with, say, Philip Jeck or Fennesz of yesteryear have some validity, but Craig’s effects, so clearly thought-through across eleven tracks, merit serious consideration on their own terms in 2018. (The Line of Best Fit)

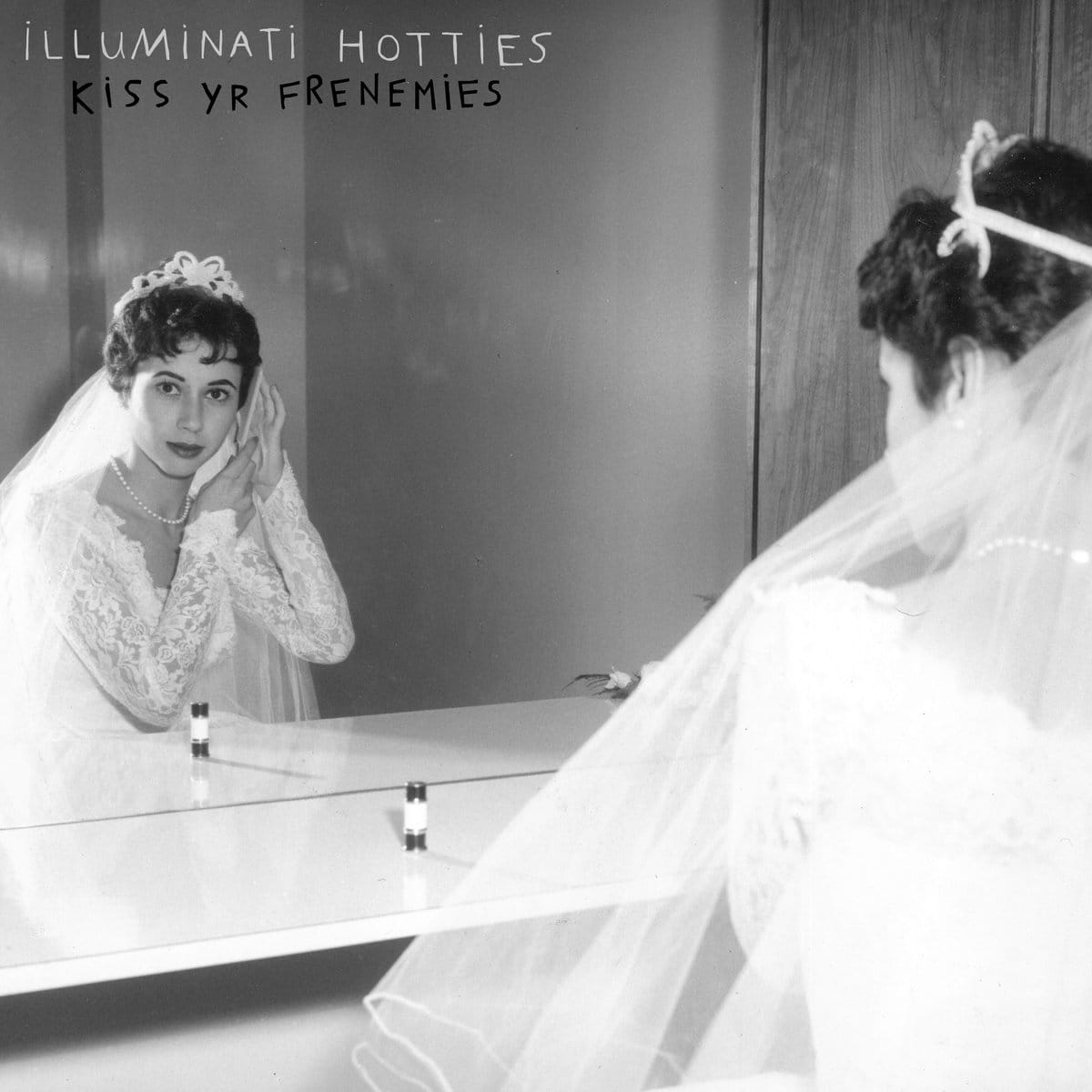

illuminati hotties, Kiss Yr Frenemies

Self-described as “tenderpunk,” the range they explore within indie and pop music is expansive. This attention to sonic detail allows each song’s production to evolve maximizing the style the band finds itself in, from pop-punk to shimmery electronics to emo shuttered acoustics. This ability to navigate sound can be attributed to Tudzin’s long resume in the studio producing prominent artists, both indie and mainstream. (Punknews)

The Internet, Hive Mind

Hive Mind remains as soulful as ever, weaving disparate sounds and textures without feeling erratic; it’s moving even at its most minimal. The Internet have grown without losing their humility. “My groove right / I might snatch up ya wife / Smooth like it’s nothin to me,” Syd coos on “La Di Da.” If you’re not married, sigh with relief. (Spin)

Jlin, Autobiography (Music From Wayne McGregor’s Autobiography)

Allowed to stretch, she explores a dripping, hard-panning, evocative ambient music made of bamboo clanks, tubular bells, ticking clocks, birds, bugs and splashing water. The intensely layered opener “First Overture (Spiritual Atom)” is like if the Matrix were rendered on Windows 95; closer “Second Interlude (The Choosing)” is a droning piece of nightmare New Age. (Rolling Stone)

The Joy Formidable, Aaarth

Throughout AAARTH, the Joy Formidable deliver a controlled aggression, tearing through heavy rockers while maintaining melodic accessibility. Bryan’s subdued vocals temper the potentially dramatic compositions, avoiding the pitfalls common to arena rock. After throwing a few punches early in the album, the Joy Formidable settle in and mix in the big rock moments with more a more colorful palette that allows AAARTH to breathe without buckling under the constriction of its harder moments. (Glide Magazine)

Julia Holter, Aviary

If Holter’s preceding records were novellas, Aviary feels more like a meticulously organized compilation of mind-altering field notes in which a single page can be a world, and its depth is stunning. Songs seem to exist within other songs. Exploring the album feels like walking through a house, where each of its 15 tracks is a room, a repository for another brilliant idea: medieval polyphony, Tibetan Buddhist chanting, the poet Sappho, Dante’s Inferno, even the outer limits of new wave. (Pitchfork)

Kasper Bjørke Quartet, The Fifty Eleven Project

Bjørke says the album follows his life during and after cancer, starting from his diagnosis in November 2011—“just two weeks before my 35th birthday”—through his final appointment in October 2016 and beyond, dealing with anxiety about relapsing. “I felt this urge to document what I was experiencing through music, but at the same time, I didn’t want to begin recording before my final hospital examination; not until I knew for certain I was going to be OK.” (Resident Advisor)

Kelly Moran, Ultraviolet

Part of the pleasure of the prepared piano—an instrument that’s been treated by placing bits of metal, wood, or paper among the strings and hammers to create phantom rattles and clangs—is its unpredictability. A clarion note may lead to another that buzzes like a broken doorbell. Moran’s compositions make the most of those contrasts, feeling them out and subtly emphasizing the muted overtones and inharmonics that are thrown off like soft sparks. (Pitchfork)

Laraaji, Arji OceAnanda, Dallas Acid, Arrive Without Leaving

As the album moves into “Somewhere Here,” the group’s pieces fuse, all their layers cohering into one. It begins simply with a single flute melody before growing into a virtual sound bath, where the beginnings and ends of every instrument blur like acid trails and seamlessly bridge into the climactic “This Much More.” (Pitchfork)

Disclosure: I’m very close friends with Dallas Acid.

Lori Goldston, Aidan Baker, Andrea Belfi, The Passion of Joan of Arc

As a follow-up to her work inspired by contemporary and historical films with her collection of non-official and interpretative scores entitled Film Scores, Lori Goldston returns with a brand new musical interpretation of the celluloid; this time, inspired by The Passion of Joan of Arc, the legendary 1928 silent film, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer, about the condemnation and punishment of the young french martyr—and feminist icon—Saint Joan of Arc. (Substrata)

Low, Double Negative

But every now and then, you come across an album that is truly startling. An album that seems to completely exist outside of any specific time and place, an album for which you have no exact frame of reference. These go beyond the albums you weren’t expecting, the ones that forge ahead in ways that take a couple listens to wrap your head around. These are albums that present as enigmas, the music therein some unholy and awe-inspiring shock to the system that can remain inscrutable for months (or years) after you’ve first come into contact with it. (Stereogum)

Lubomyr Melnyk, Fallen Trees

The inspiration for this album’s title, and for at least six of its tracks (including the final five, all part of a linked suite), came from Melnyk’s journeys across Europe in recent years. Glancing out of a train window when traveling through a gloomy forest, Melnyk’s vision was arrested by the sight of felled trees. “Even though they’d been killed, they weren’t dead. There was something sorrowful there, but also hopeful,” he comments, in the process aptly summing up the atmosphere conjured up by much of his recorded output. (Drowned in Sound)

Lucrecia Dalt, Anticlines

Rushing and slowing unexpectedly, her voice moves like eddying floodwaters seeking a vacuum to fill. In the background, hard-panned clusters of tones sound more like pools of light than notes; a high whine could be air escaping from a leak. The album’s title refers to a kind of geological formation, but Anticlines has more in keeping with the properties of matter as it shifts from liquid to gas and back: It’s an album full of interstitial forms that flicker in between fixed states, and its magic lies in that liminal no-man’s-land. (Pitchfork)

Makaya McCraven, Brandee Younger, Tomeka Reid, Dezron Douglas, Joel Ross, Universal Beings

We’ve been here before, in awe of the drumming, bandleading, and exploration of Makaya McCraven... Many of McCraven’s releases are edited recordings of live sessions, so it would stand to reason that his latest album would be along the same lines. McCraven’s new joint...corrals four different groups in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and London for groove-heavy live sets that will continue to be the earworms one expects from this drummer for likely the next two or so years this will stay in your rotation. (Nextbop)

Mary Lattimore, Hundreds of Days

The shift and its itinerant power are clear from the very first minute of Hundreds of Days, during the exquisite “It Feels Like Floating.” Lattimore frames an ascendant, patient harp line with spectral vocals that recall the solo symphonies of her friend and collaborator Julianna Barwick or even the luxuriating sounds of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. This feels, indeed, like floating—and also like watching the setting sun filter through the towering trees, seeing the morning sun bathe an immense mountain range, or most anything you experience where all you have left to do is sit and wonder. This is a veritable sky of sound. (NPR)

Masayoshi Fujita, Book of Life

Whilst Book of Life expands the palette of Fujita’s compositions, he still manages to find ways to experiment with the vibraphone to create new sounds and textures. On ‘Fog’ Fujita plays the vibraphone with a cello bow, to produce these soft sustained notes that give the track a mournful, lonely tone, whilst a second vibraphone plays a slow melody. The album’s title track, meanwhile, sees Fujita scratching the bar of the vibraphone which combines with chimes to create this tension between the abrasive and the delicate. (The 405)

Matchess, Sacracorpa

Despite its dreamlike blissfulness and immersion, Sacracorpa is more sparse than lush. Every single one of the few elements that are present feels necessary and important, from the soft pulses of rhythm to the new-agey synths and even occasional nature recordings, and this purposeful simplicity is what makes the music so profoundly intimate. (Noise Not Music)

Meg Baird, Mary Lattimore, Ghost Forests

Progress through these tracks gives the sense of an odyssey that could never be repeated. If you replay these tracks immediately after the first spin you’ll notice new landmarks, altered points of reference, and a kind of life that wasn’t first made obvious. A third spin offers yet another account of the journey. Like Jim Jarmusch’s movie Dead Man there’s a sense of inevitability about conclusion, a beauty in loss of direction—because all directions lead to the same destination. (popbollocks)

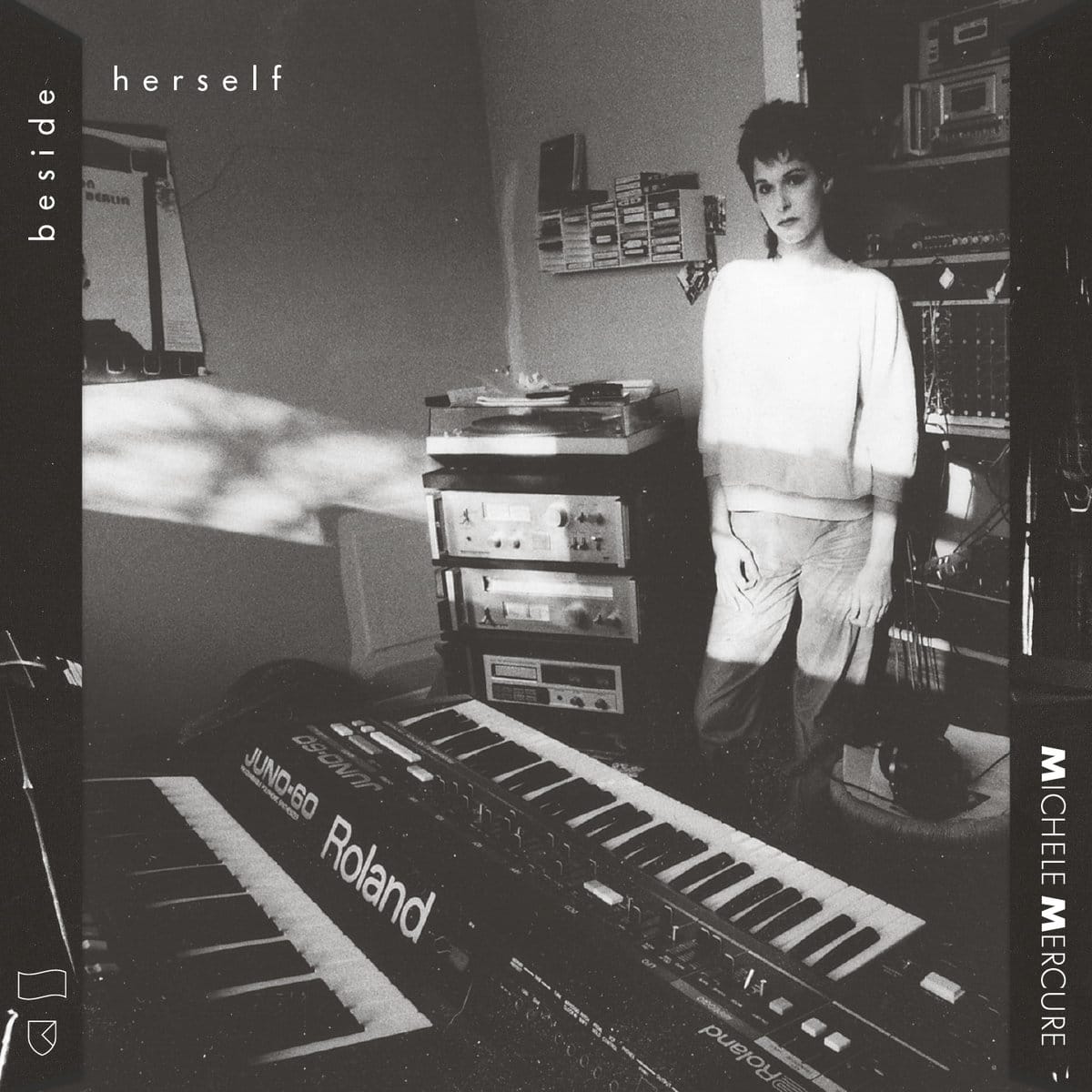

Michele Mercure, Beside Herself

But it’s the pieces on Beside Herself that Mercure composed for the stage that are the most compelling: “Antigone,” which was recorded for a version of the Sophocles classic, sounds as brooding, violent, and sinister as the play itself, long, ribbonlike notes twisting and turning. On “No More Law in Gotham City,” which was originally commissioned for the performance artist Mary Gast, the words “Pictures on your screen are coming to us live,” are repeated in different pitches and speeds while an ominous, sweeping synth creates an atmosphere of unease. (Bandcamp Daily)

Mick Jenkins, Pieces of a Man

One can’t help but fall in love with the intro of this album, “Heron Flow” (featuring Julian Bell). On the track, he begins like an artist who knows he’s about to snatch the souls of listeners with his lyrics. He starts by saying: “My name, of course, is Mick Jenkins … and we are here this evening to give you some free thought. Some food for thought.” Meanwhile, on “Gwendolynn’s Apprehension”, he continues to spread the wisdom: “Can’t teach and young nigga, he don’t want to know / Could be a flower, he don’t want to grow.” As most rappers his age aim to draw attention to themselves, Jenkins opts to focus on the message and the audience who needs to hear it most. (Consequence of Sound)

Mitski, Be the Cowboy

But these complexities only emphasize the point Mitski returns to on each of her records: love is manifold. Romance is all consuming and breathtaking; intimacy can be a cycle of toxic stillness. Be the Cowboy is a definitive statement on the myth of perfection. She can stretch to the heavens and sink into the ground. She can be everything at once, again and again. “I thought I’d traveled a long way / But I had circled the same old sin,” she gravely bellows on “A Horse Named Cold Air.” To the two elderly subjects of the devastating closer “Two Slow Dancers,” all those complexities can be relieved beneath the glow of a disco ball. In the album’s last breaths, the spotlight slowly fades from Mitski. She might be exhausted, but she is insatiable. (Pitchfork)

Name Sayers, Mantles

Name Sayers’ debut LP spins a torch-lit ritual of loud, gothic post-folk led by a singer whose hovering baritone and metaphysical command position him as the musical next of kin to Nick Cave and PJ Harvey (had the onetime lovers ever procreated). Eight scriptures from the ATX four-piece unfold with the tribal, floor-tom pounding of “Upbringing,” over which Devin James Fry chants a creation story where his body and voice are a macrocosm of the Colorado landscape: “Yarrow grow where my heel go / Red canyon down my back.” (The Austin Chronicle)

Nils Frahm, All Melody

All Melody is an ambitious ambient-electro-acoustic creation that will still sound vital 10 years from now. It’s also a sublime starting point for those unfamiliar with this multifaceted musician. With his new creative “kitchen” in place, we can only wonder what delights Frahm might deliver next from [his new studio] Saal 3. (NPR)

Noname, Room 25

Well-rounded without ever coming off as formulaic, Noname succeeds at introspection while questioning the world around her. Rapping slightly quicker than the spare funky bass line and steady drum tempo of “Blaxploitation,” she flaunts her ability to tackle a number of topics on a whim—sprinting from fast food joint Chick-fil-A’s controversial anti-LGBT stance to gentrification to Hillary Clinton’s pandering to minority communities during her 2016 election run. (Spin)

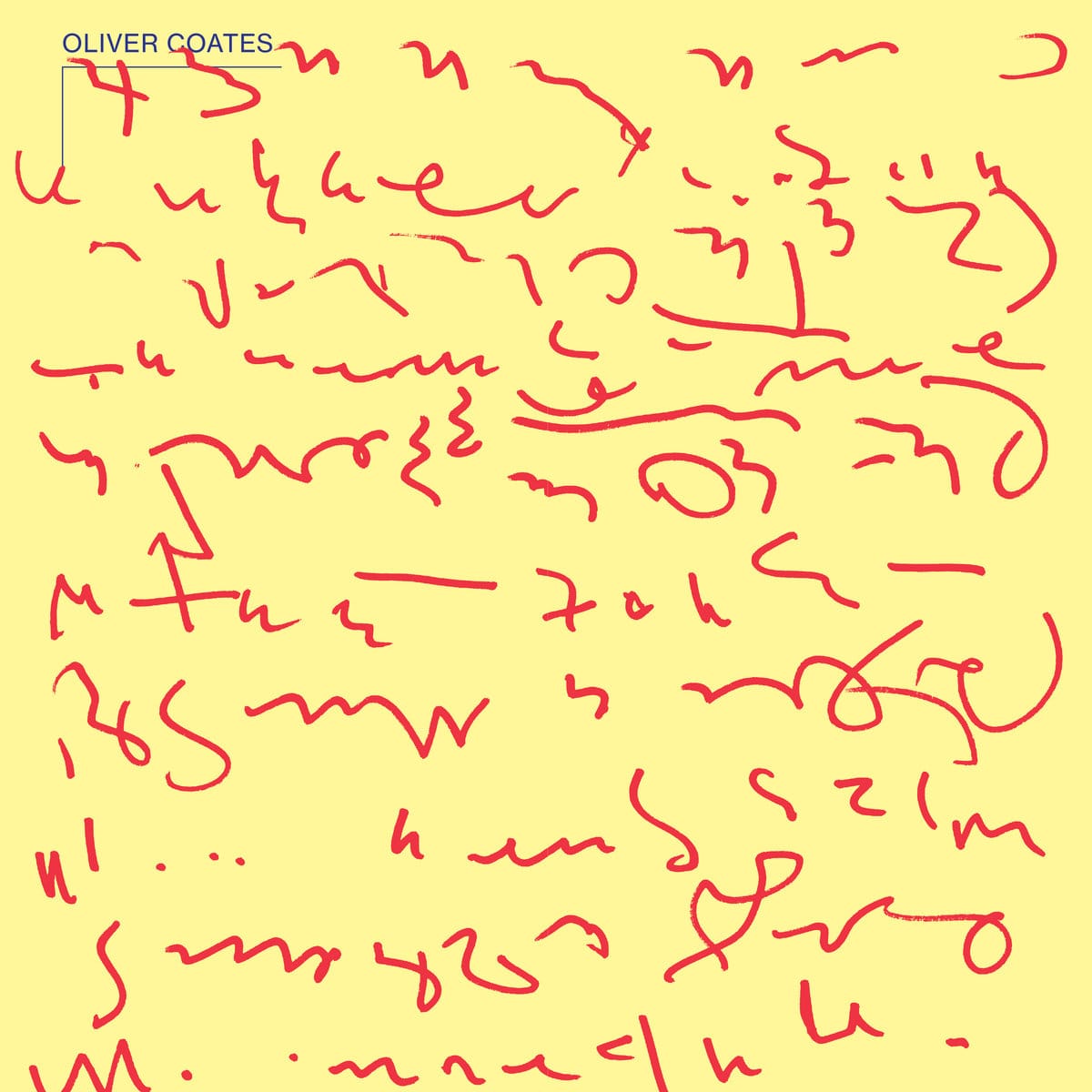

Oliver Coates, Shelley’s on Zenn-La

But unlike a lot of music made in Aphex Twin’s wake, Shelley’s never sounds overly reverent. On the contrary, it is playful and exploratory—the rare example of “experimental” music where pleasure seems to be at least as crucial as process. The interplay between contrasting textures—scrappy drum samples, brass-synth squelch, ethereal wordless vocals—is a source of constant fascination. Track lengths range from 95 seconds to nearly nine minutes, and in every case, the duration feels natural, a factor of Coates discovering exactly what he wants to say and then moving on. (Pitchfork)

Power Therapy, Warmth for Bad Skaters

It is difficult to overstate the influence of a small set of bands in the 1980s and 1990s spearheaded by Sonic Youth and My Bloody Valentine. Their ability to fuse old-fashioned studio-generated noise with sweet melodies is a strong link in the chain that connects the Velvet Underground to today’s avant-garde... An exciting new album from Jonathan George Fox pulls the two sides of that great period in music—the noise and the melodies—and places them side by side. The album’s notes describe Warmth for Bad Skaters as “an ode to unspoken interactions, constant audio distractions and his former home in North London.” (Badd Press)

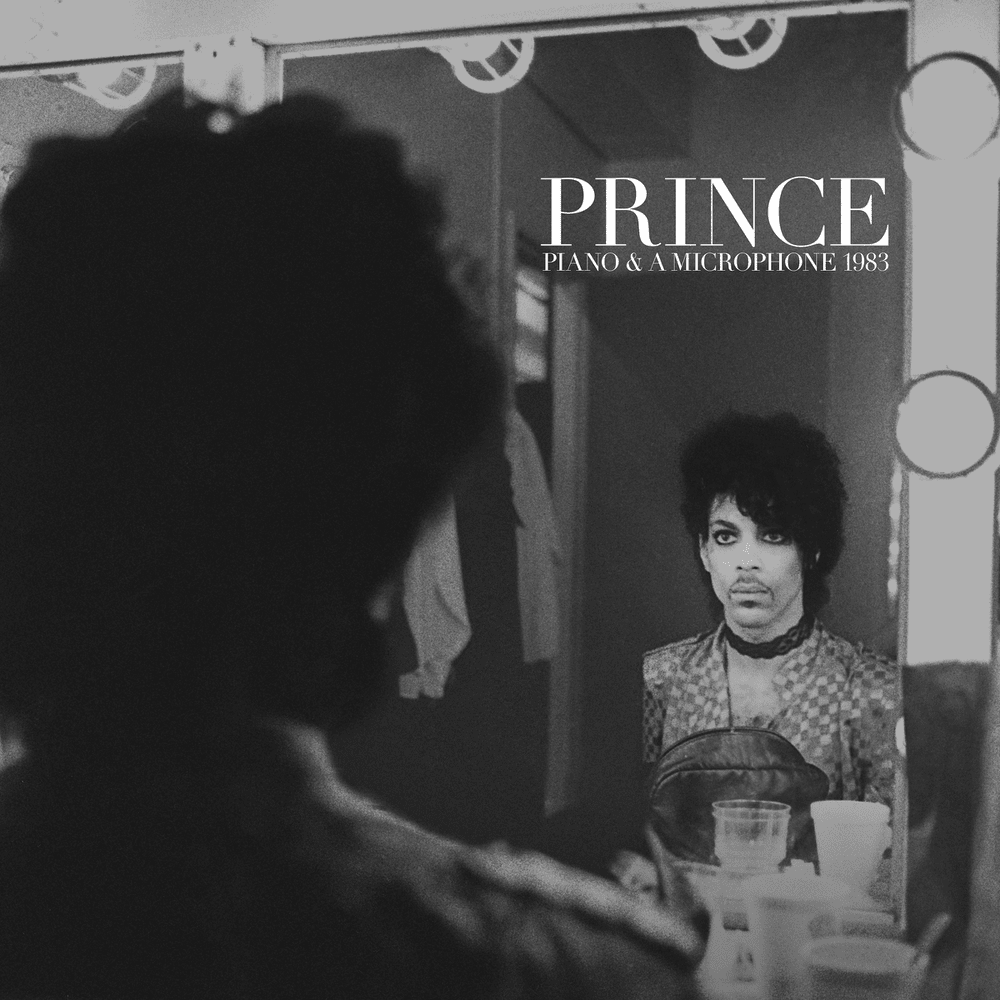

Prince, Piano & A Microphone 1983

The “new” material on Piano & a Microphone has already circulated as bootlegs, but this album clarifies its details, rescues it from indistinct hiss. The most surprising moment is when Prince begins playing the gospel standard “Mary Don’t You Weep,” a song that must have been absent from all his potential tracklists, even ad-libbing fraught lyrics: “I don’t like no snow, no winter, no cold.” Fingers slinking over his piano with heavy steps, vocals slurring at the edges, he gives the spiritual a physical force. “There has always been a dichotomy in my music,” Prince once said. “I’m searching for a higher plane, but I want the most of being on earth.” Piano & a Microphone is both omen and artifact, a rehearsal for another life. (Pitchfork)

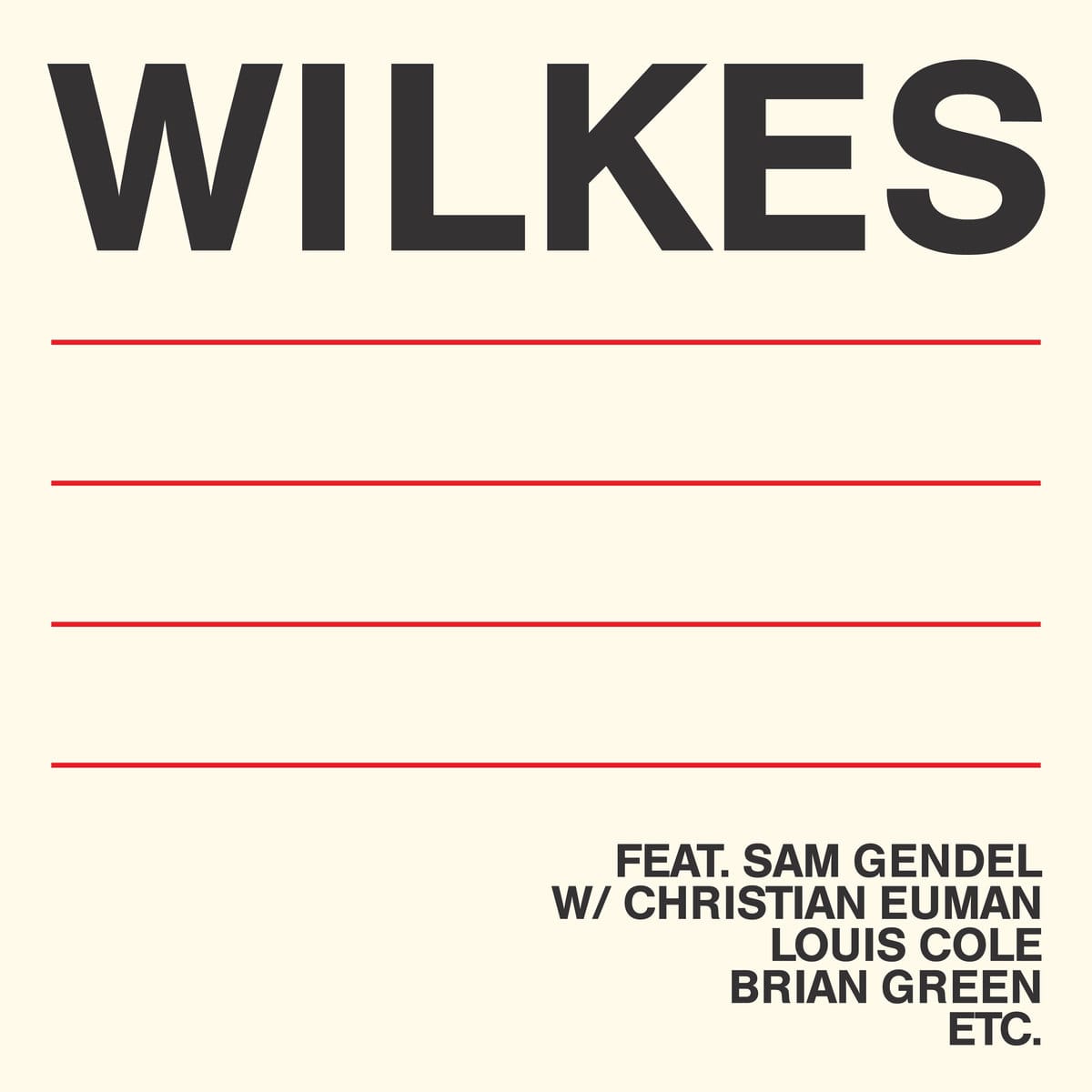

Sam Wilkes, Sam Gendel, WILKES

Wilkes deviates from this relaxed mood to create a variety of textures. “Hug” begins with sonic chaos, as electronically altered vocals bellow beneath a frenetic drum performance by Christian Euman and Gendel’s sax. After about four minutes of auditory freak-out, the song calms down as Euman’s drums fade away leaving Gendel and Wilkes alone in the electronic soundscape. The focus on songs and creating a cohesive mood instead of instrumental theatrics plays to this album’s strengths, making this a solid project by a great up-and- coming artist. (All About Jazz)

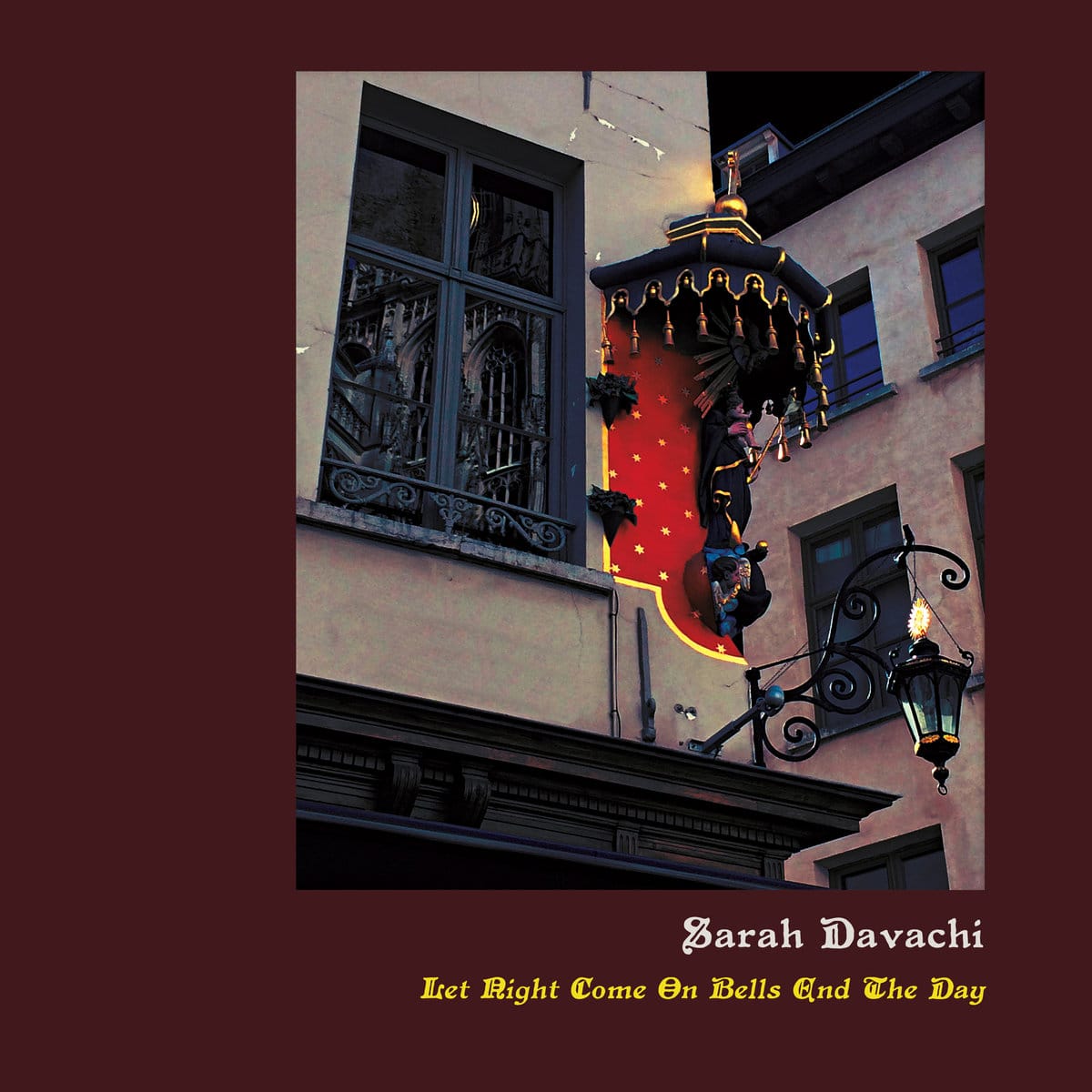

Sarah Davachi, Let Night Come on Bells End the Day

The results highlight the romantic potential in Davachi’s ostensibly academic method. The record is an “homage” to her background as a keyboard player, which might explain its creeping nostalgia, expressed in sepia coloring and occasional dog ears of distortion. (An accompanying film from the recently deceased Paul Clipson puts Davachi at one remove from another purveyor of shadowy nostalgia, Grouper.) The album title, meanwhile, might refer to the artist’s preference for working at night. There’s no doubt that its hushed, meditative compositions are suited to the witching hour. Recital boss Sean McCann nailed the ideal listening situation: “A blanket, a cup of wine, a dim bulb, a wide window.” (Resident Advisor)

Sarah Davachi, Gave in Rest

It would be over-simplistic to cast Gave in Rest as simply an album for being alone with. There is, however, an undeniable air of blissful inner peace that comes from absorption within it. This is music that captures the atmospherics of the early music with which Davachi has become increasingly fascinated: music that was often inherently spiritual in its compositional practice and intent. This album may not be the work of a religious individual, but it aptly communicates the sense of religious fervor that often resides within the act of composition, not to mention the act of listening. (Drowned in Sound)

Sumac, Love in Shadow

Despite being 65 minutes long, there’s an organic and careful pacing to the album that makes this feel like a shorter listen. The record sounds great, too—it’s deep, rich and immersive, perfect for this type of meditative journey. Most impressive is the diverse range of noise that streams from the guitars. At times, the record sounds like a damned hybrid of psychedelic-rock, noise, drone, and death metal. Every shard of sound from Turner’s guitar—particularly in “Attis’ Blade”—can be heard murmuring, moaning and shivering through the mix. (Angry Metal Guy)

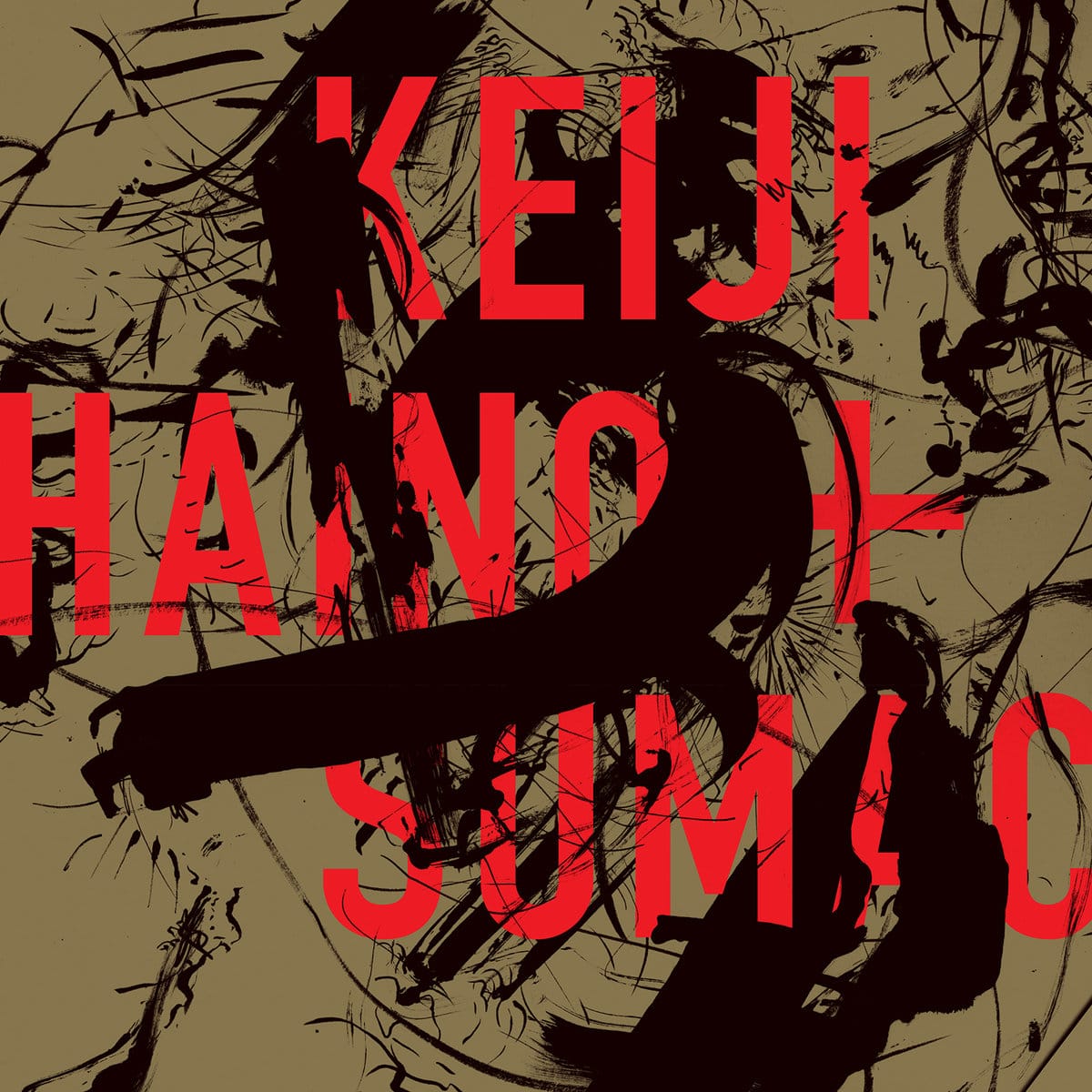

Sumac & Keiji Haino, American Dollar Bill—Keep Facing Sideways, You’re Too Hideous to Look at Face On

Sumac were already playing slow and loose with structures before, and Haino obliterates any sense of form. His orthodoxy is that there are no orthodoxies, and so Sumac’s lumbering doom becomes an endless outburst of wahs and scrapes. “What Have I Done?...”—a track whose full title runs to 43 words, and which gets split into two parts on opposite ends of this album—has some of the band’s most volatile clusters, rife with overlapping guitar freak-outs and escalating drums. The sound falls in line with Fushitsusha, Haino’s long-running free-rock band, at their most chaotic, and it also recalls the noisy, disassembled grindcore of Sissy Spacek and Burmese. (Pitchfork)

Szun Waves, New Hymn to Freedom

Though I spend several hours a day listening to music, it’s rare that I come across a track that forces me to pause whatever else I’m doing and just listen. “Fall Into Water,” the second track on Szun Waves’s New Hymn to Freedom, does just that. It’s built around a simple, comforting three-note drone pattern, overlaid with subtle layers of bells, percussion and a restless oscillating synth line, and listening to it feels like staring into a bonfire—that state of being lost in a trance, all the while mindful of the creative and destructive capabilities of the elements. (The Quietus)

Tim Hecker, Konoyo

Hecker remains irreducible as a composer. At times, he brings to mind an ice sculptor, carving out staggering shapes from giant blocks of sound that feel crushingly heavy even as they seem to melt away. Some moments here echo the early ’00s series Clicks & Cuts, others Arthur Russell’s World of Echo. You might also hear the elegiac rise and fall of Stars of the Lid, an emotional Hollywood score or William Basinski’s sound of decay. However, as Konoyo unspools, you may look back and realize that this all combines to sound like no one other than Hecker. (Resident Advisor)

William Basinski, Lawrence English, Selva Oscura

From what I can surmise, the two pieces on Selva Oscura—the titular track, running nearly 20 minutes, and “Mono No Aware,” clocking in around 19 minutes—are very “un-Basinski” in the way that they do not build toward something and then slowly begin to decay and fall apart. They are both works that are in constant motion—similar to the lengthy, multi-movement pieces from Andrew Hargreaves’s Tape Loop Orchestra project—meaning that things are regularly shifting throughout, as it leads to some kind of resolution. (Anhedonic Headphones)

Yonatan Gat, Universalists

Yonatan Gat’s Universalists presents a bold new idea for what to do with rock: treat your own band noise like other people’s samples and weave it into something bigger. Gat, late of Tel Aviv’s Monotonix and now based in New York, spends a lot of this record kicking up clouds of guitar dust with drummer Gal Lazer and bassist Sergio Sayeg. But a nearly equal amount of space is taken up by vocals, either sampled or courtesy of Rhode Island’s Eastern Medicine Singers. All of this is treated as a single slab of sound for Gat to slice and dice in the studio, and the surface of this terrifically organic music is rearranged electronically in unpredictable ways that suggest Teo Macero, DJ Screw, Yeezus-era Kanye, but not much else in rock music. (PopMatters)

Yves Tumor, Safe in the Hands of Love

Everywhere on Safe, violence mingles uneasily with delicacy—Tumor’s own voice switches from a wraithlike falsetto to a yell to a menacing chant. All of it feels too close—mixed too close in our headphones, clipping into distortion, but also too close for comfort, the massive sounds looming over the delicate ones. “Have you looked outside? I’m scared for my life,” Tumor pleads on “Noid.” This is music aware of oppressive confinement, and music with an intoxicating urge to be free. (Pitchfork)

Originally published at The Morning News