The Top Albums of 2019

Ninety-three albums that sounded like this year

Everything here presents some kind of new idea or feeling, something that felt ike it pushed the medium one step (or many) further in one direction (or many), and I hope there’s stuff in here you like as well. Recommendations came from all over: readers, newsletters, blogs(!), RSS feeds, social media disinformation campaigns, Spotify robots, and SoundCloud mixes. (And for those of you who enjoy these picks, I’m starting a new thing in 2020 with more of this, more often.)

Here are playlists of all 93 albums on Spotify and Apple Music as well as song picks—one from each album—on Spotify and Apple Music.

Thanks for listening, and Happy New Year.

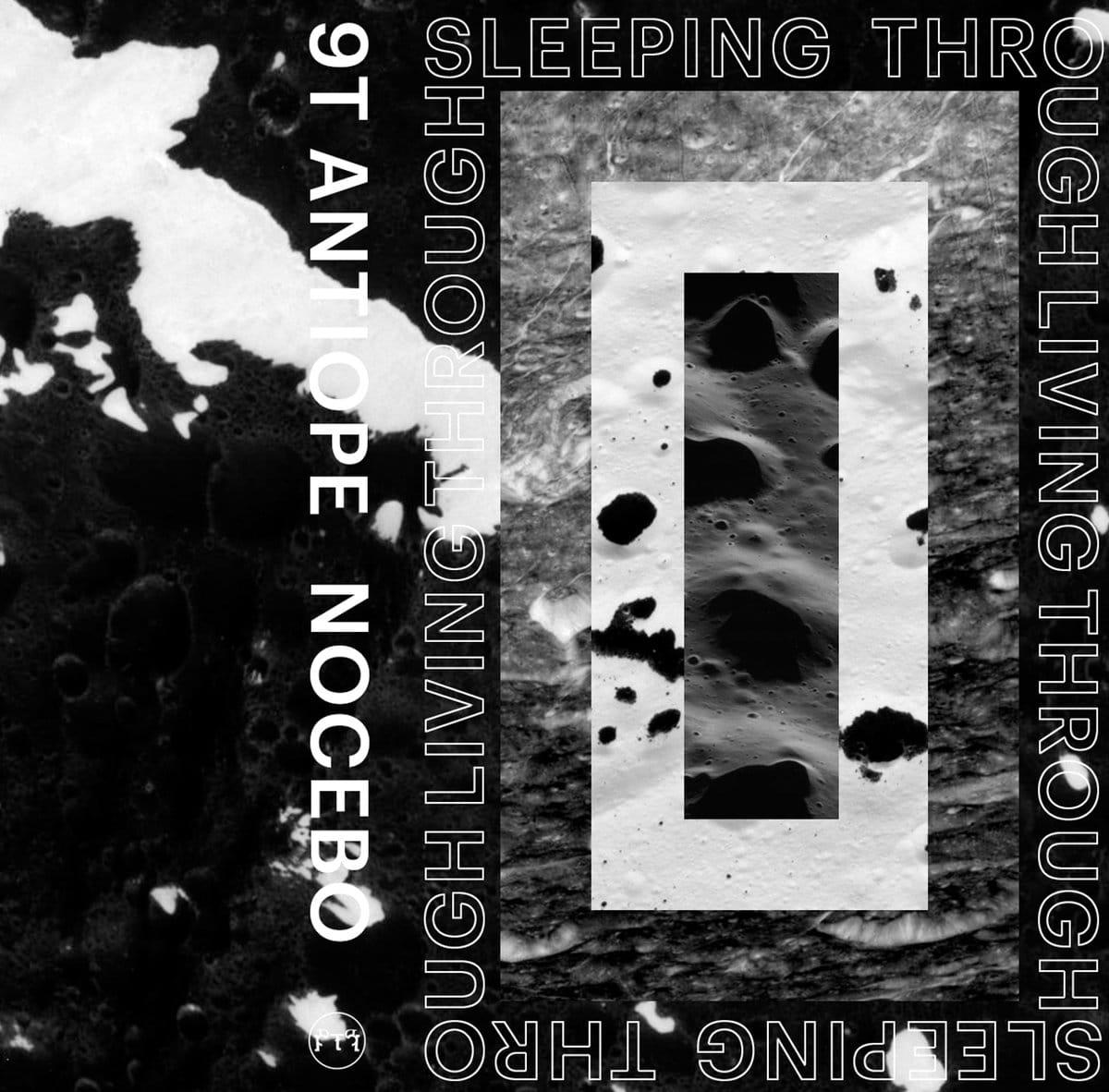

9T Antiope, Nocebo

The tape’s second side begins with a monologue, focusing on bodies, senses and self-awareness, as if somewhere within the cocoon life is continuing to grow. For a few minutes, it seems that the track will continue to be reclusive. Then a distorted call to prayer is answered by warlike percussion, joined by saws and beeps, the former sounding like truncated dogs. Is this the sound outside the dreamer, from which one has retreated; or the sound inside the dreamer, the knot of guilt and obligation that might cause one to reengage? (A Closer Listen)

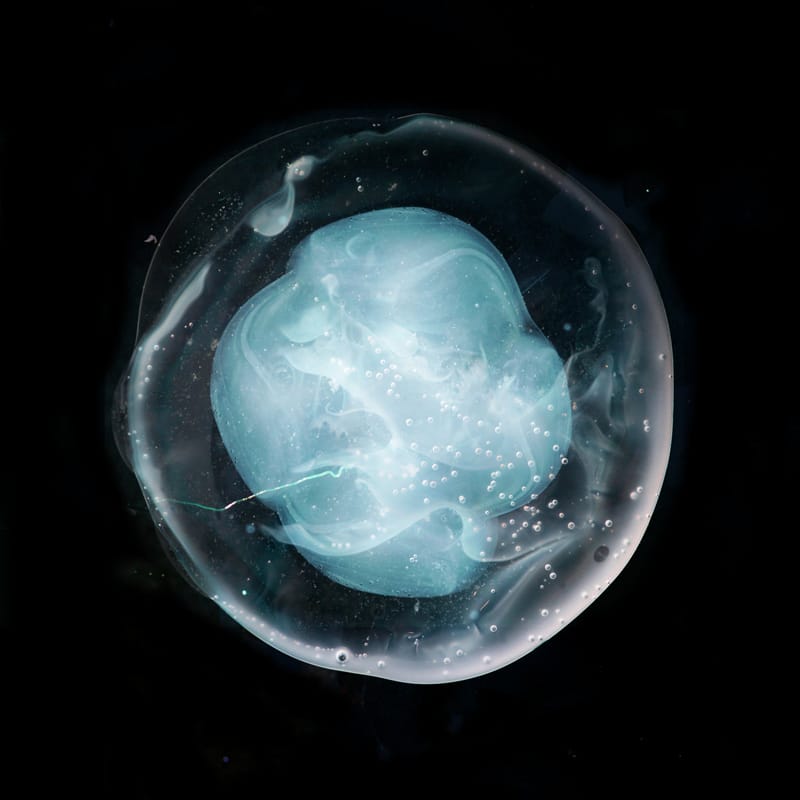

A Winged Victory for the Sullen, The Undivided Five

The flowing compositions may sound simple but the intricacies are skillfully executed and are borne from a slowly oscillating backdrop of subtle swells and subdued cadences. Majestic harmonies and orchestrated melodies rise to the surface through a hypnotic matrix of processed strings, synths, and piano. The leisurely pace of the music can lull the listener into a dream-like state, but the shimmering beauty of the layered, symphonic delights commands attention so the listener gets taken on a musical excursion into the peaceful inner spaces of rich ambient soundscapes. (Under the Radar)

Amar Lal, Gardening

Like watching a time-lapse of grass growing or ants working, the record’s opening track “Privilege” is a metamorphosis, the start of something new and cyclical in its awakening. It’s a warm fog rolling in as the ocean ebbs and flows at the shore. It’s getting lost among the tallest of trees with no concept of time or place. However you like to imagine it, Amar Lal’s music feels like a de-stresser, an escape from the grind of city life and working jobs we hate. It’s a peaceful mediation of beauty trickling in from the floor boards, and it’s only the start of his stunning collection. (Post-Trash)

Ami Dang, Parted Plains

By nature, then, these fragments can be an intense listen, especially on the compositions inspired by the four tragic romances of the Indian region of Punjab. On “Sohni” (named after the tale of Sohni Mahiwal, who drowned crossing a river to her lover), Dang layers multiple sitar tracks to evoke the swirling cacophony of water, while “Love-Liesse” uses oneiric, gently pedalled strings to evoke reunited lovers. (The Guardian)

Andy Stott, It Should Be Us

The feel of the line at the beginning of “Dismantle” is similar, part Detroit techno, part ’80s adventure movie—but what follows is an illustration of just how far an inspired producer with a taste for adventure can travel. As a listener, it’s like you mistakenly took the wrong drug. The experience you’re expecting reveals itself to be something else entirely, the walls of the track caving in with every smack of Stott’s cruel, 70-BPM kick drum. The synth returns, all bright and optimistic, but you can’t forget the horrors you’ve just heard. (Resident Advisor)

Anna Meredith, FIBS

Even before “Nautilus,” Meredith seemed predestined for this terrain, with one foot in pop and another in new classical, and choreographing those limbs to brilliant effect. Her catalog—a solo for bassoon amplified like punk guitar; a Steve-Reich-meets-Stomp “Body Percussion” orchestral piece; an IDM mash-up of a brunch classic, etc.—is recommended to anyone bored by much of what passes for contemporary repertoire. After “Nautilus,” Meredith’s pop miniatures also reflected an art-school nature. It’s in her non-traditional instrumentation and songwriting, whose complex structures and crisp lyrical narratives have precedents throughout the UK’s post-punk, art-prog, synth-pop timeline. (Pitchfork)

Bill Callahan, Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest

This is not an album for just throwing on in the background while surfing social media (or even reading this review). Before putting it on, make sure you have an hour to yourself to just let it wash over you. Callahan’s ambition and essence haven’t been diminished by him being in a good headspace. He’s a man born to tell stories, and he’s no less of a storyteller than he was in his early 30s. (Consequence of Sound)

Black Dresses, Thank You

The lyrics continue their fatalistic streak, death-obsessed while also espousing a sense of community—as they put in one of the tracks, if we’re going to be going to hell, “let’s go to hell together.” There’s songs about how we’re fucking up the earth and letting down the people in it, about dreaming for a better world, about thinking things can’t get worse until they do. (Stereogum)

Blacks’ Myths, Blacks’ Myths II

This plot is underpinned by music only slightly less grand—and engages a pair of debates being waged inside the jazz and noise/punk communities these two musicians call home. The central questions here are “What is it?” and “Who is it for?” One springs from a new generation of players reassessing jazz’s structure, language, and storied place within the African American tradition. The other is forcing punk to figure out how to embrace its black roots and ascertain its musical purpose in a Trump-era cauldron. (Pitchfork)

Blood Orange, Angel’s Pulse

Angel’s Pulse demonstrates the most appealing aspect of Hynes’ apparent restlessness: a broad gush of musical ideas and influences. In its opening two minutes, it dramatically switches styles from old-fashioned C86 indie to something not unlike Drake’s Auto-Tuned R&B, albeit drained of the bullish machismo that underpins Aubrey Graham’s poor-me solipsism. Elsewhere, there’s hypnagogic pop decorated with improvised sax; gloopy chopped-and-screwed hip-hop; heaving guitars in the vein of My Bloody Valentine; a track featuring mask-sporting rapper-cum-social media sensation BennY RevivaL that sounds as if it was taped off an untuned radio. (The Guardian)

Carlos Niño, Carlos Niño & Friends, Bliss On Dear Oneness

The seventh Carlos Niño & Friends release is a mixture of improvisations and layers of overdubs, forming what the composer calls “space collage music.” The pieces document in-the-moment outpourings of cosmic energy, sometimes mixing disparate sounds with seemingly no obvious connection, and rarely having proper beginnings or endings. It can get formless and soupy at times, as on opening track “Pulsating,” an ultra-trippy mélange of crickets, rushing water, brief synth flashes, and third-eye visions. However, the more focused selections are truly magnificent and inspiring. (AllMusic)

Caroline Shaw, Attacca Quartet, Orange

Shaw is inspired by more than just the classic composers. In a piece called “Limestone & Felt,” she imagines herself in a Gothic cathedral, where shards of melody bounce off the walls and intertwine. In another, “Valencia,” she creates an ode to the noble, store-bought orange, marveling at its architecture, its tiny sacks of juice explode via a pulsating spray of plucked notes. (NPR)

Cate le Bon, Reward

But during those moments of self-doubt and struggle, there’s a thread of persistence that runs throughout Reward. “I love you but you’re not here/ I love you but you’ve gone,” Le Bon sings on the album’s masterful first single “Daylight Matters,” which even in its central absence feels hopeful. Le Bon holds onto a sense of playfulness despite the loneliness. “Mother’s Mother’s Magazines” purrs and whirrs and traces the lineage of the women in her own life: her mother and grandmother and those beyond that, looking at how they’ve lived with their own pain and strife and survived. “Did not see the comedy of decline before,” Le Bon sings there, with a screwy and maniacal glee. (Stereogum)

Caterina Barbieri, Ecstatic Computation

Some compositions on Ecstatic Computation gesture to the divine. “Arrows of Time” is in the style of a medieval choral piece, featuring vocalists and what sounds like a harpsichord. It would sound at home performed in a gothic cathedral. But it’s the album’s tension between control and chaos that best evokes ecstatic states. If Barbieri’s last album was defined by subtle shifts meant to tranquilise and hypnotise, Ecstatic Computation is marked by sudden breaks from predictability. Stylistic influences and sonic textures are varied, yet they’re cohesive. The result is an album that’s both provocative and blissful. (Resident Advisor)

Charles Hayward, (Begin Anywhere)

I first heard Charles Hayward play “Watching You,” the first track of his new solo LP Begin Anywhere, at This is Not This Heat’s electrifying reunion show at the Barbican in 2017. Anticipating the full onslaught of “Horizontal Hold,” it was surprising and disquieting even when Hayward appeared first to play a ghostly, austere solo set; a stark, solitary presence alone at a piano. Used to hearing Hayward’s voice as the sole human emissary from within the strange, dissonant sonics of This Heat or Camberwell Now, it was confounding to hear his voice so bare, so vulnerable, so immediate. (The Quietus)

Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, Ancestral Recall

Inasmuch as it invests in rhythmic expansion, Ancestral Recall also marks a turn inward. It is an exciting strategic choice for stretch music, the philosophy born of cultural amplification and group interplay. It almost feels like a hint that simply playing the changes—no matter how many different kinds, or with how broad a cast—is no substitute for understanding how to live through them. (Pitchfork)

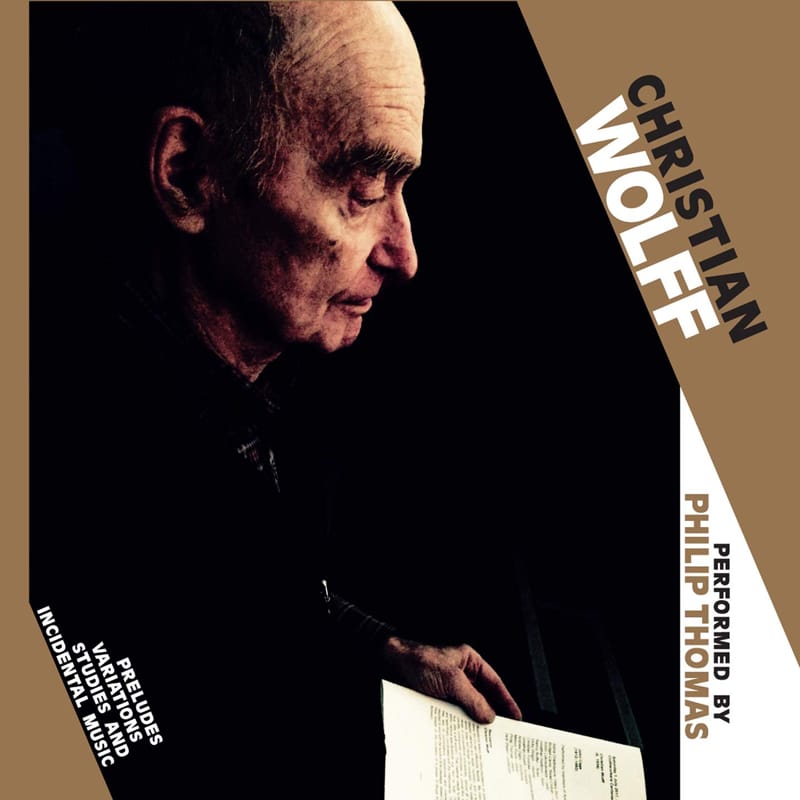

Christian Wolff, Philip Thomas, Preludes, Variations, Studies and Incidental Music

These two discs reveal Christian Wolff as a composer fully exploring, in different ways, the continuum between music which is highly fragmented, embracing extended silences (composed or indeterminate), to that which is more progressive and seemingly driven, albeit taking in disarming and unconventional routes. As a body of repertoire, these works are remarkable for their freshness of musical thought and energy (John Cage considered Wolff to be the most “musical” of the experimental composers). (Forced Exposure)

Clams Casino, Moon Trip Radio

There’s a clear arc throughout the album, and by the midpoint, Clams—who used to source new sounds by typing search terms like “cold” and “blue” into LimeWire—is offering some of his warmest-sounding music. The songs are as sonically destroyed as ever, bristling with digital flotsam and tape hiss—see “Twilit”—but the patient harmonic changes give the doomy atmospheres a certain sentimentality. Chopped breaks and angelic electric piano noodling on “Cupidwing” and “Fire Blue” invoke the lovelorn works of DJ Shadow, while “Lyre,” with its lonely guitars and wildlife recordings, reframes Clams as hip-hop’s own Daniel Lanois. (Pitchfork)

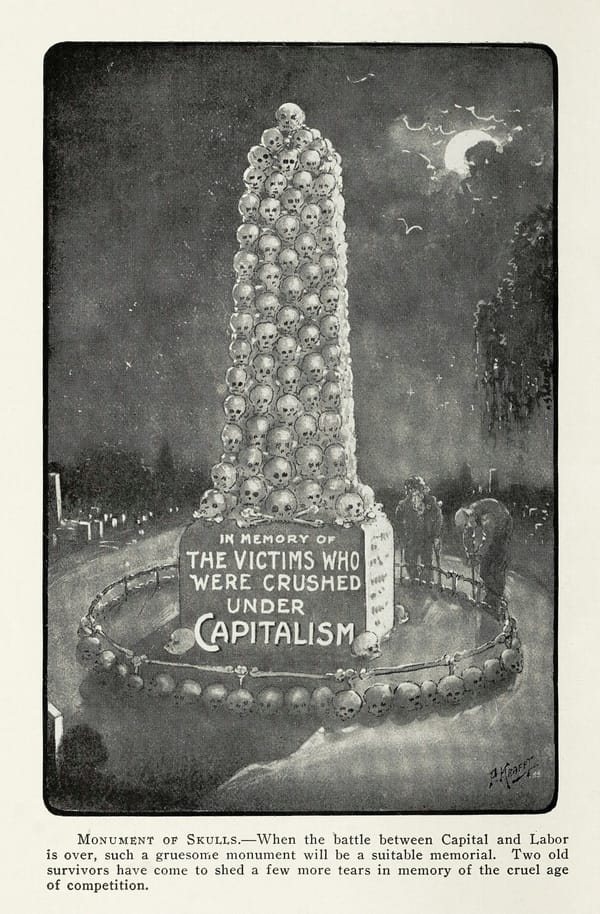

clipping., There Existed an Addiction to Blood

There Existed An Addiction to Blood, Clipping’s new album, is a meditation on the idea of horror — horror movies, horror stories, ’90s horrorcore rap. On the different album tracks, Diggs lays out different gruesome movie scenarios. Rich people pay piles of money to watch poor people die horribly. Someone hides from mysterious pursuers in a dumpster. A tryst becomes a bloodbath. We’ve heard stories like this before, but that doesn’t make them any less unsettling. And Diggs lays these stories out with bloodthirsty delight, zooming in on detail, digging into the texture of the viscera: “A signal fire in the lymbic nerves / Gotta give the kill what the kill deserves.” “The bags on the table ain’t for weight, they for body parts / Victim’s skin stretched across the wall, call it body art.” “Steve was still there on the floor, what was left of him / Gnarled bone, body parts, all piled in a mess.” (Stereogum)

COLOSSAL SQUID, Swungert

Chaos isn’t just a theory on Colossal Squid’s debut album; it’s a state of being. Creator Adam Betts maintains the anarchy for nearly 36 minutes straight, without resorting to backing tracks or leaning on laptops most of the time. Computers are merely cogs in the tool kit Betts has built around his beloved drum set on this record—a master class in man-versus-machine dynamics which blurs the line between the two entirely. (Bandcamp)

Cosey Fanni Tutti, TUTTI

Tutti has what she’s called a “built-in aversion to repetition,” and she doesn’t stay in one mode for too long. “Sophic Ripple” progresses ominously with buzzy synths that build and retreat like waves. The effect is at once calming and foreboding, with a quiet bassline hinting at a beat without ever coming to the fore. The album surprises throughout—Tutti’s voice, rippled and soft on “Heliy,” lends the record a tactile humanity. Layered behind bubbly synths and crackling sequencers, it is a quiet suggestion of authorship, or presence—a reminder of the woman behind the record’s vast soundscapes. (Resident Advisor)

Croatian Amor, Isa

The album feels more like a series of waves than a collection of songs. It crests on relative bangers such as the heart-tugging “Point Reflex Blue” and a minimal club track, “Dark Cut,” both coming into circuitous but muscular rhythms. Rahbek’s beats seem to go forward and backward at the same time, as if the air is hissing out of a balloon. (Pitchfork)

Crudo Pimento, Pantame

But even as a first encounter with Crudo Pimento, the song’s Lynchian ambient bookends—soft strings, keening voices—indicate that there is more to this duo. Whizzing through 13 tracks in 29 minutes, Pantame takes in 1990s-inspired alternative rock, glitching electronic percussion, the dread empty spaces of post-punk, and an overdriven blast of live jazz improv that sounds as if it were recorded on a waterlogged Dictaphone in a blast-cratered nightclub. (Pitchfork)

Dallas Acid, The Spiral Arm

Arising from largely improvised performances that accompanied a cosmic expedition at San Antonio’s Scobee Planetarium, The Spiral Arm ranks not as the Austin ambient trio’s spaciest effort—that’s 2016 debut Original Soundtrack—but as their most beautiful. (The Austin Chronicle)

Disclosure: I’m close friends with this band, but don’t let that stop you from listening to them.

David Allred, The Cell

Across seven stately tracks—some short, some long, but all handsome—he offers thoughtful reflections on love, life and loss. It’s never really his voice, figuratively or literally, that’s the star of the show; instead, what stands out about Allred’s songwriting is his ability to craft an emotional ballast so effectively. There are no words on the album’s centrepiece, “Full Moon,” just hums, whistles, and a sea of reverb that packs a thumping emotional punch. (Loud and Quiet)

Deaf Center, Low Distance

A total masterpiece for anyone inspired by the fine details stitched in a microcosm of harmonies and timbres. One which I will treasure for the many years to come, and with these words I hope you’ll too. Highly recommended for anyone delighted by reductionist pianism, isolationist ambience, coarse minimalism and granular spaciousness. Yes, I’ve authored some of those stylistic genres just for you. (Headphone Commute)

Deantoni Parks, AUGUSTA

Working with John Cale, Sade, Flying Lotus, and the Mars Volta, Deantoni Parks’ beatmaking skills on just a drum kit and sampler remain astounding. A collage of cut-and-paste BPMs and samples, this year’s Augusta traverses pocket grooves (“Manganese”), hi-hat experiments (“Chrome Snare 1977”), and speedy footwork (“Bass Drum 1966”). (The Austin Chronicle)

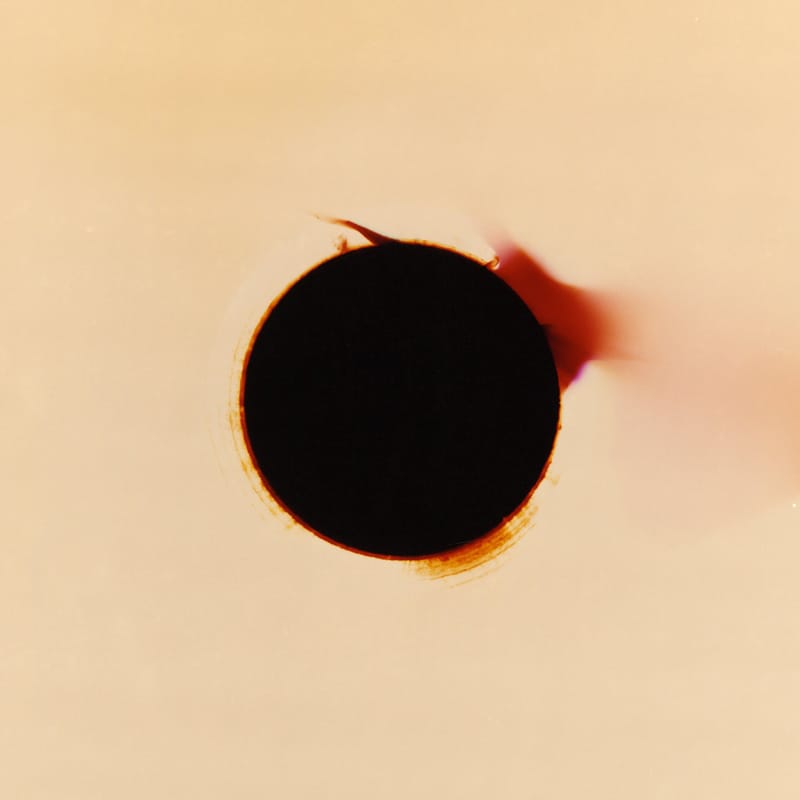

Deathprod, Occulting Disk

Despite the truculent introduction, Sten does much more than rage. His emotional breadth and nuance remind us of the heart required to fight back. “Occultation 2” suggests the onset of a panic attack, with meticulously nested layers of static and sustain closing in around you, cutting off your ability to consider anything else. With its delicate tones drifting above air-raid sirens, “Occultation 3” evokes a mourner’s wail amid chaos. (Pitchfork)

Deli Girls, I Don’t Know How to Be Happy

I relate all this both to demonstrate that they are real grinders—it kinda feels like you could see Deli Girls every weekend if you had the will and means—and that they’re skilled navigators of the blurry, ecstatic, dangerous spaces between established sounds and scenes. Live, Kelly bashes out these busted up beats and samples that feel equally of a piece with Ronny J’s running-through-a-brick-wall rap beats, Suicide’s broken noise loops, and the crushing fuzz of hardcore. Orlowski meanwhile half-screams, half-raps, half-yelps lyrics about trauma, violence, revenge, and the police state. They shred in any circumstance. (VICE)

Dissemblance, Over the Sand

Over the 10 tracks Dissemblance treads the fringes of a blurred dream world, using her bass guitar, voice, and drum machine as the backbone to create haunting yet soothing pop atmospheres in her songs. (Bandcamp)

Doon Kanda, Labyrinth

Labyrinth is not just a musical project; it comes complete with ten visual works, showing Kanda’s emphasis on world-building. The characters rendered in those works are smooth and slick, made of something like flesh or polished stone. The winged figure on the cover of the album is bone-white and pocked with cavernous holes, windows into an inside that’s largely empty. There’s a softness in its pose that counteracts the uncanny form; though it stands erect, its head is slightly bowed, hands gesturing toward prayer. That softness manifests in the music, present in the sweeping, darkly sweet melodies of “Nastasya” and “Bunny.” In these moments of pleasure with discomfort hovering beneath, Kanda reaches synthesis between his visual and musical universes. (Pitchfork)

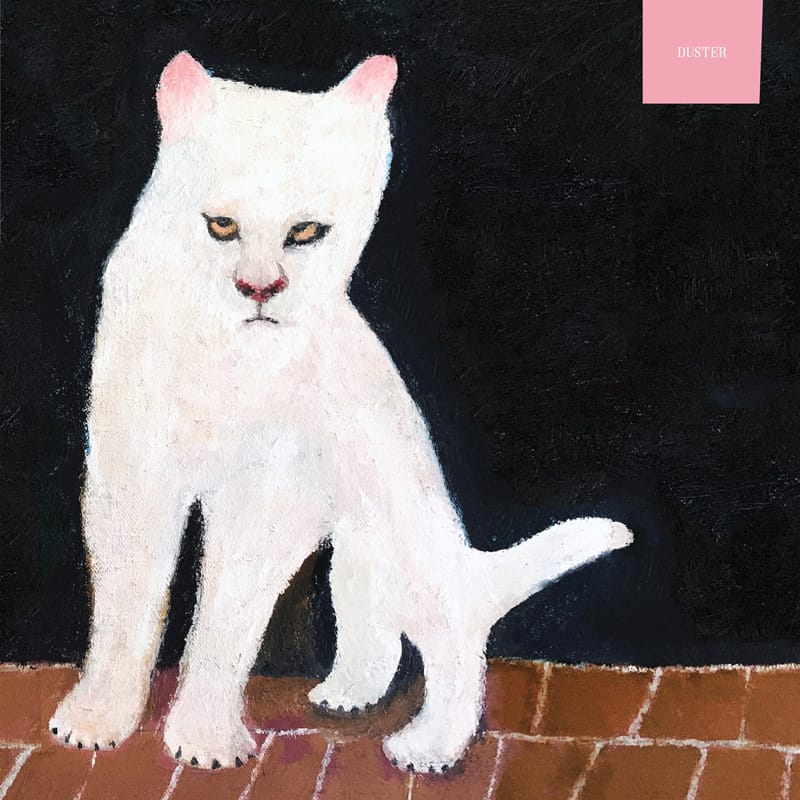

Duster, Duster

Duster have never been easily defined. They’re too urgent for “slowcore”, too meandering and weird for “indie rock”; they’re cited as major influences on their peers yet remain relatively unknown, compared to old label-mates Modest Mouse and Built to Spill. Yet when all the pieces align, they sound as transcendent and otherworldly as the cosmos they’re so fond of. (Independent)

Ellen Arkbro, CHORDS

As I was walking I heard the piece, during one of its more sparse moments, oscillate intensely. I felt dizzy, disorientated: I paused. It became clear that my walking itself had caused the shift: the subtle changes as my headphones moved on my head, or as my head moved in them, my feet connecting to the ground, making waves. Now looking around, unmoving, I had an overwhelming experience of calm that is difficult to put into words—a small moment of stillness and emptying out while listening. (The Quietus)

Empath, Active Listening: Night on Earth

There is rarely a time where things seem settled in the world of Empath, however a connection always remains between the band as the seamlessly play off each other and the rampant emotions. There is rarely a moment of peace on this record as it appears to be on the verge of a breakdown most of the time, yet there remains a joy in a necessary release. This record delivers quite a gut punch, and a powerful one at that, and as an expression of joy, pain and honest emotion is a beautifully breathtaking piece of craftwork. (Post-Trash)

Felicia Atkinson, The Flower And The Vessel

“Moderato Cantabile” is a good example of how Atkinson builds her more complex, multivalent sound worlds. The piece progresses like a cloud being blown by the wind, imperceptibly morphing into different shapes and never returning to any single, solid form. “The Linguistics Of Atoms” shows how Atkinson uses silence and space to achieve a similar effect. The second half of the piece is especially stripped down, but creates a sense of immense unease through the use of short, dissonant plinks of piano and marimba, juxtaposed with a high-pitched ringing that feels just at the edge of the audible range. In this context, her voice, when it appears, feels alien and unnerving. Still, the listener is drawn into the most minute details of the composition. (Resident Advisor)

Fire-Toolz, Field Whispers (Into the Crystal Palace)

It’s hard to name any composers—at any level of the industry—who are more “more is more” than Marcloid. The stems for these eleven tracks must be more like redwood trunks, so layered, complex and multidirectional are the resulting arrangements. It’s electronic at root, and subject to heavy digital processing of course, but with live guitar and bass—fretless, for that extra injection of jazz fusion—chopped up, post-FlyLo or perhaps post-post-Squarepusher style. Marcloid’s loose links to the nebulous vaporwave scene repeatedly manifests, too, cuts like “April Snowstorm (Idyllic Mnemonic)” touting MIDI-melancholy keyboard melodies and smarmily ersatz woodwind. (The Quietus)

Floating Points, Crush

The album’s title, says Shepherd, is not to do with a romantic yearning, but with the helplessness of contemporary inevitabilities: climate change and self-serving politics. His signature cosmic lightness is often married here with weightier sounds: the urgent UK bass on LesAlpx; the slowburning elegance of Karakul juxtaposed with dissonant glitches; Bias pairs lithe garage beats with an eerie melody. Beautifully crafted, Crush unsettles with its quiet, fervent chaos bubbling beneath its surface. (The Guardian)

Forest Swords, The Machine Air (Original Score)

Barnes’ score, presented here sculpted and edited into 14 individual tracks, echoes the film’s cyberpunk claustrophobia: smeared sci-fi synth and distorted melodies rattle alongside metronomic rhythms and stretched samples, rewiring the hums of flying vehicles into warped and contorted sound design. Intimate piano melody weaves with sub bass, while woozy electronics and strings mirror the fluttering of the machines as they hover skywards, powering up and down. (Boomkat)

Gavilán Rayna Russom, The Envoy

By so intrinsically folding Le Guin’s novel into this album, Russom widens the impact of her central idea. Conceptual records like this, where notions of being transgender are creatively framed and expressed, can encourage further reading and more empathy. It’s a step towards a better understanding—the same thing Le Guin’s envoy was striving towards and that Russom is exploring. The album doesn’t draw definitive answers. But asking some questions and framing some thinking can be helpful in its own way. (Resident Advisor)

Girlpool, What Chaos Is Imaginary

And in a way, the same things that drew me to Girlpool in the first place are still there on What Chaos Is Imaginary. They’ve just taken different forms. That first EP sounded to me like an album about friendship, about the intense way that kids can cling to each other when they’re just figuring things out. The moving part was the way both of their voices became one. On What Chaos Is Imaginary, the moving part is the way their voices layer over each other, alternating or quietly backing each other up. They don’t sound like they’re clinging to each other anymore. They sound like they’re helping each other out, but like they’re both on their own, wandering and figuring things out. That’s a different kind of friendship, but it’s no less important, and it’s no less moving. (Stereogum)

Greys, Age Hasn’t Spoiled You

The record is full of surprises, something we don’t often get to say about rock music in 2019. The single “Kill Appeal” kicks off as a driving post-punk cut propelled by blast beats before it crashes and erupts into free jazz. “These Things Happen” and “Western Guilt” recall the spaced-out psych pop of early Blur. Maybe the most striking, however, are opening tracks “A-440” and “Arc Light.” The former serves more as a test pattern than a proper tune, intertwining static thrums and whispers and a shrill buzzing. “Arc Light” cuts through “A-440”’s disintegration with squeals that could be either be from an effects pedal or whales in distress, instantly recalling My Bloody Valentine’s “Touched.” Tiny details are embedded throughout the record, enriching reminders of process and precision. (Pitchfork)

Helado Negro, This Is How You Smile

The album closes with “My Name Is For My Friends,” a track titled to recall Kincaid-esque parental advice. It’s filled with the ambient sound of a birthday party — maybe the one depicted on the album’s cover featuring a young Lange and his brother. “This is how you smile to someone you like completely,” Kincaid wrote. (NPR)

Helm, Chemical Flowers

The album begins forebodingly with what sounds like bells tolling during a screaming firework display. This confusion is part of the appeal: Younger discovers new musical worlds, leaves them untitled, and burrows into them until their origins become blurred. Only a musical savant could work out where the blurts and scrapes are derived from; this is the unknowing fun of it all. On the rippling “Body Rushes,” drone-laden synths wash across your brain for three ecstatic minutes. When he taps into these frequencies, like on the majestic title track that closes the eight-track project out, noise eclipses silence as the soundtrack to tranquility. (The Quietus)

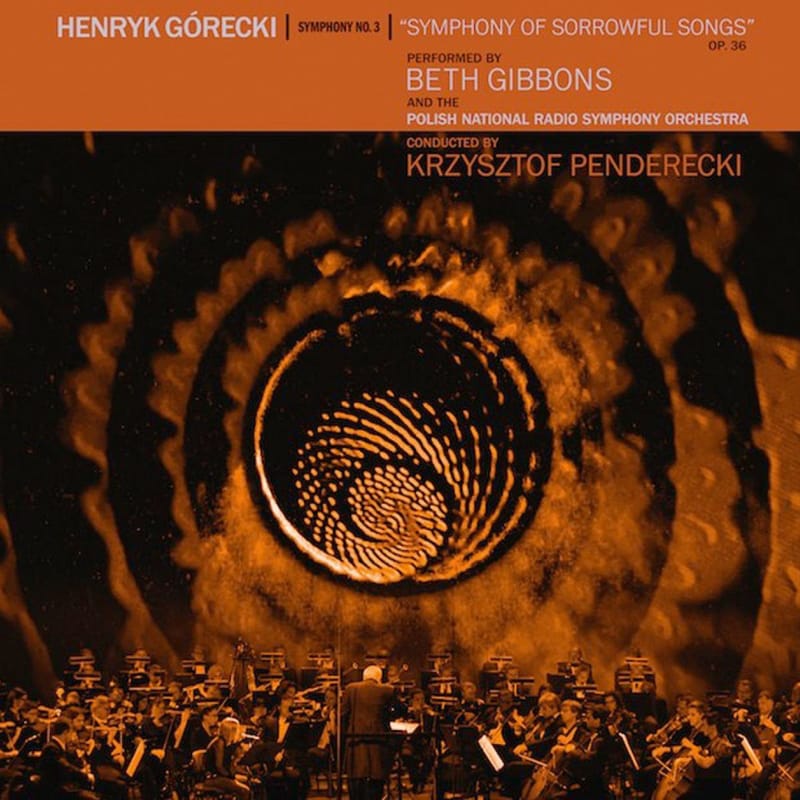

Henryk Górecki, Beth Gibbons, Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Krzysztof Penderecki, Henryk Górecki: Symphony No. 3 (Symphony Of Sorrowful Songs)

And now comes Beth Gibbons—the voice of Portishead, and thus, by extension, the purveyor of trip-hop’s most vivid bad moods. Gibbons is not a powerful singer in the athletic sense—she’s never going to threaten the structural integrity of a chandelier. But her grainy, sour wail, coated with streaks of dried spilled coffee and nicotine stains, strikes deep chords of clammy fear, of desperation, of vulnerability. Her voice, from the moment it arrives over the breath-bated haze of strings in the first movement, is arresting and close to your ear. Symphony No. 3 has a nightmarish undertone that tends to get smoothed out in dulcet recordings—one of the texts is meant to be the sound of a woman calling out for her murdered child—and Gibbons brings that squirming danger right to the surface. (Pitchfork)

Holly Herndon, PROTO

PROTO is Herndon’s most technologically adventurous work to date, but it is also by far her most ecstatically humanistic. One of its most stunning and revealing moments comes on “Frontier,” a work inspired by Appalachian Sacred Harp singing, an a cappella tradition originating in American Christian communities. A single unadorned voice runs through a scale, as if leading a vocal warm-up; on the last note, a chorus of human and machine voices joins in. The sound undoubtedly stems from human throats and yet it is serrated and compressed in a way that could only have come from digital processing. But the seam between the two is not clear. There is no artificial layer to peel back, no true voice underneath plastic coating. Ninety seconds into the song, vocal notes shudder into a riff. The natural glissando of human singing dissipates; there is one note and then there is another, with no passageway between them, yet the music does not sound inhuman. It sounds like a new kind of human vocalizing, augmented by machine, not reduced by it. (Pitchfork)

Human Feel, Andrew D’Angelo, Chris Speed, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Jim Black, Gold

“Imaginary Friend” was conceived by Speed with vigorous, eerie vibes and assertive instrumental attacks such as the machine gun-like bratatat of the guitar, intense saxophone interplay, and magnetic prog-rock-derived pulses. This is one of the many pieces influenced by the alternative rock genre, having the particularity of carrying shades of erudite dark metal. Other hard-hitting rock ambushes are made on D’Angelo’s danceable, post-punk-influenced “Eon Hit” and Black’s “Stina Blues”, which sounds more American garage than dirty grunge. Also, “GD” falls into a stationary darkwave with the reedists blowing ostinatos in counterpoint. This occurs during the tune’s last section, which comes in the sequence of a quieter passage patterned by marvelous sax melodies and lush guitar chords wrapped in relaxing synth effects. Later on, it’s Black’s infallible dynamics that come to prominence without ever sounding off the marks. (JazzTrail)

Jenny Hval, The Practice of Love

The Practice of Love reveals the sensitive humane core that was always behind Hval’s practice of enlightened dissent. The album develops an elegant approach to solving the existential problems of love, care and intimacy from the position of otherness. Hers is a margin taking over the centre. For all its epic signalling, the romantic immediacy of love as a disruptive big bang-like event is here missing, the title proving to be a bait. Instead, Hval harnesses the subversive power of gentleness. (The Quietus)

JPEGMAFIA, All My Heroes Are Cornballs

What makes it effortless where earlier exercises (like the infamous police shooting-sampling “I Just Killed a Cop Now I’m Horny”) felt consciously edgy is how defined Peggy’s sound and persona are now. On lead single “Jesus Forgive Me, I Am a Thot” he’s cocky and camp, alternately acting as his own adlib-spouting hype-man and warbling back-up singer. His production responds accordingly, drawing parallels with pop music hooks and bridges before descending into outright delirium. (Under the Radar)

Julia Kent, Temporal

At 12 minutes in length, opening track “Last Hour Story” loops echoing pizzicatos atop droning melodies and electronic murmurs. It’s a study in how simple melodies and ever-growing musical layers can simultaneously convey dread and intrigue. What the track lacks in variety it compensates for with a meditation on texture and resonance. By contrast, “Imbalance” fuses mournful melodies with skitters and throbs more akin to dance music, yet the result never sounds cheap or forced. Kent understands how unites these disparate elements that respect their source material while presenting them in an entirely new context. (PopMatters)

Ka Baird, Respires

Baird’s latest album is enveloping and overwhelming. Her breath, recorded at close range and often oscillating quickly between the left and right channels, becomes sweeping and absorbant, augmented with electronics and sparse instrumentation that add to the feeling of disorientation. Listening on headphones, one can hear looped flutes shooting back and forth, darting melodies braiding over each other. Short gasps coalesce into propulsive rhythmic patterns, which shift and mutate around the listener. One of Respires’ definitive features is Baird’s ability to make each sound seem omnidirectional, emerging from many angles in quick succession. (Resident Advisor)

Kim Gordon, No Home Record

Above this maelstrom, Gordon presides. Fully embracing her role as a no-wave Joan Didion, Gordon spends the most fruitful parts of No Home Record dissecting American illusions; her deft attacks hit targets from the emptiness of aspirational luxuries (“Air BnB”) to gentrification (“Don’t Play It”) with artful barbs that manage to provide critique without lapsing into fuddy-duddy lecturing. There’s real economy in these lines, with “Don’t Play It” getting the best of the bunch; here Gordon raves like an aging prophet sick of spelling things out, offering criticism (“Used to have a gallery/ Now it’s just a floral shop”) and humor (“Where are my cigarettes?/ Those aren’t my brand!”) from breath to breath. (Consequence of Sound)

KOKOKO!, Fongola

The band formed at a local block party in their Ngwaka neighbourhood in 2016 and were brought into the studio by French producer Débruit, who had made his name with four experimental albums that referenced Haitian hip-hop and Turkish folk. Thankfully, the recordings preserved their sense of spontaneity: their 2017 debut single Tokoliana combines snappy electronic percussion and pulsating kick drums with amorphous synths and vocals that veer from guttural refrains to stifled screams of joy. Fongola—also produced by Débruit—keeps up the street-party energy and develops it, adding Kokoko!’s unique mix of DIY instruments such as bottle percussion and three-stringed guitars. (The Guardian)

Little Simz, GREY Area

Simz flips between two tones: bristling and unapologetic, and warm and reflective. “Offence” is the former, with tongue-in-cheek bars that have her hailing herself as “Jay-Z on a bad day, Shakespeare on my worst days”. So, too, is “Boss”, with its killer bass hook and distorted punk vocals. Elsewhere, she considers the impact of her own ambition: “Wanting to be legendary and iconic, does that come with darkness?” she asks on closer “Flowers”, reflecting on her idols Jimi Hendrix and Amy Winehouse. (Independent)

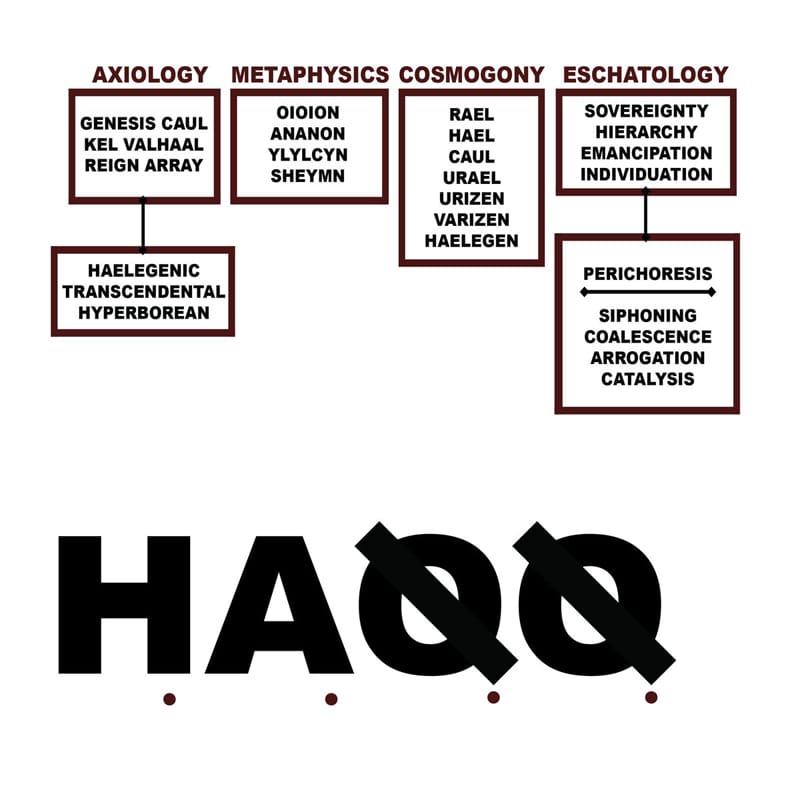

Liturgy, H.A.Q.Q.

Listening to the album is like balancing on a wobbly stool, trying to reach something on the top shelf, never quite getting there, but being very aware the entire time that you could fall. At certain points, it feels as though the album is about to self-destruct, contorting to the point of almost combustion. There’s an immense feeling of fragility, of vulnerability, but also hope and expectation, the painfully self-aware Hunt-Hendrix knowing that, without this vulnerability, he can’t grow. (Everything Is Noise)

Loraine James, For You and I

James’s music is hyperactive. Even the album’s gentler tracks, like “Scraping My Feet,” have skittering drums, which twirl around slow, woozy melodies. There’s a constant tension between anxiety and joy that manifests in tracks like “Glitch Bitch,” where ballroom-style vocals bark against a placid backdrop, or “Hand Drops,” a song inspired by the risk of queer public displays of affection, in which rough basslines scrub against beautiful, floating melodies. (Resident Advisor)

Lunacy, Age of Truth

In short, Age of Truth is like entering a rabid storm cloud. Electrical forked lightning slashing across in every direction. Beneath you, great sheets of rain empty downwards, forming the world’s highest waterfall and you are there, lost within it, no longer able to discern how the hell you are supposed to get out. In this respect the whole record is an apt metaphor for the feeling of impotent malaise that seems to have currently been thrust upon our sick and stifled societies. (Echoes and Dust)

Mary Halvorson, John Dieterich, A Tangle of Stars

Mary Halvorson and John Dieterich’s first collaborative album, a tangle of stars, released on artistically diverse label New Amsterdam Records, unfolds across a wide range of musical styles. “Drum The Rubber Hate” is the first new piece on the record, composed by Halvorson, a 2019 MacArthur Fellow and prolific solo guitarist, improviser, and bandleader. It’s an upbeat, dreamy track, built from the layering and repetition of melodic fragments. Starting in unison, it forks into fuzzy electric guitar melodies and detailed improvisational solos, all played over layering of the first thematic material. Here, Halvorson’s signature fluid improvisational jazz is a powerful force amongst the more rock-oriented soundscape. “Drum the Rubber Hate” shifts into the woozy sonic landscape of “Balloon Chord,” also composed by Halvorson, where detailed, alternating guitar plucks echo into a hazy sea of sound. (The Road to Sound)

Michael Gordon, Deborah Artman, Michael Gordon: Acquanetta (Chamber Version)

The music that accompanies this vision has that repeated, assaultive scraping sound you associate with horror movies (Bernard Herrmann’s score for “Psycho,” in particular). A melding of human voices and shrieking strings, it’s a full-throttle scream transformed into pulsing melody. And it’s enough to make the hairs of even a slasher-flick devotee stand on end. (The New York Times)

MIKE, Tears of Joy

As with all of his music, tendrils of swirling, foggy noise suffuse Tears of Joy, giving the songs patterns that can be held onto, while opening up breathing space between the glowing samples and MIKE’s elliptical writing. There’s a distorted film sample (“GR8FUL 2K19”), the droning, rap-free, Duendita-featuring “#Memories,” abrupt beat switch-ups (“Scarred Lungs, Vol. 1 & 2”), and extended intros and codas that sound plumbed from fantastically weird, immaculately-produced beat tapes. (The Fader)

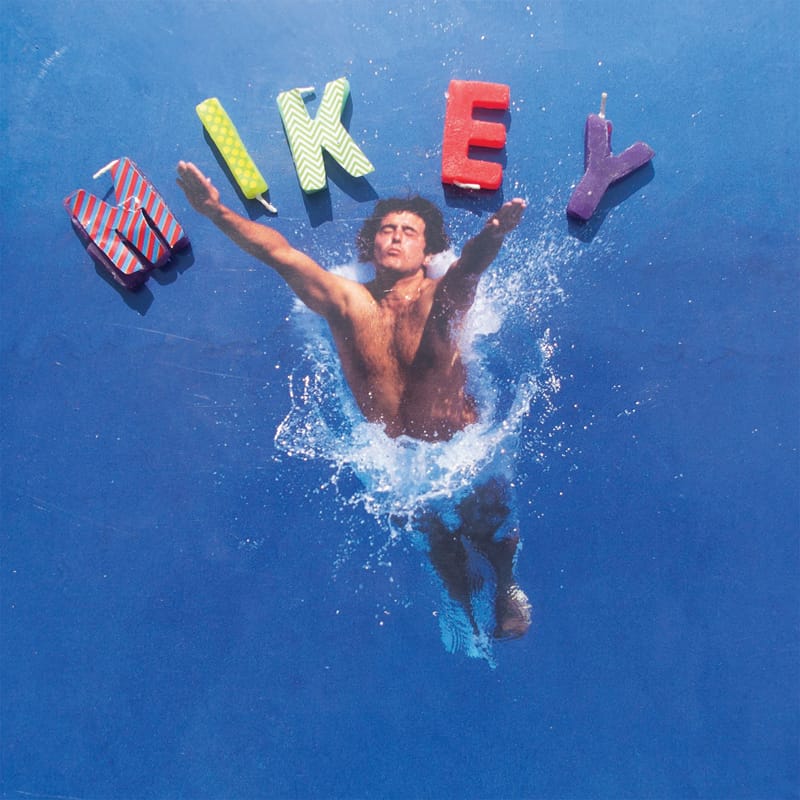

Mikey Young, You Feelin’ Me?

With You Feelin’ Me?’s broad palette, Young flits from the woozy strums and underwater gurgles of his opening eponymous track, while gliding seamlessly to the robot jazz oddity of “This ↑” and then to the 80’s sci- fi burbles on “Billions of Tears.” The Melbourne native creates a sound that’s both aloof and engaging; for example, “Life on the Perimeter” sounds like Daft Punk and Kraftwerk embroiled in a jazz-funk-space battle, while the urgent bounce of “it’s Walkable” invokes the jittering strut of jungle music, as played by retro cyborgs. (Northern Transmissions)

Moor Mother, Analog Fluids of Sonic Black Holes

From the opening track “Repeater,” Moor Mother lays out this world in stark terms, one of enslavement, murder, and repression: “Over our head, repeater, deceiver… by nation, by parliament, by ritual of wealth / You hold death over our head / you hold life over our head / I hope you get what you’ve been giving out / I hope you choke on all the memories. No light, just insecurities, false hope and enemies.” These words are accompanied by brooding strings and ritualistic incantations that create a heavy, sulphurous air of invocation that launches the album out on its journey and reckoning. (The Quietus)

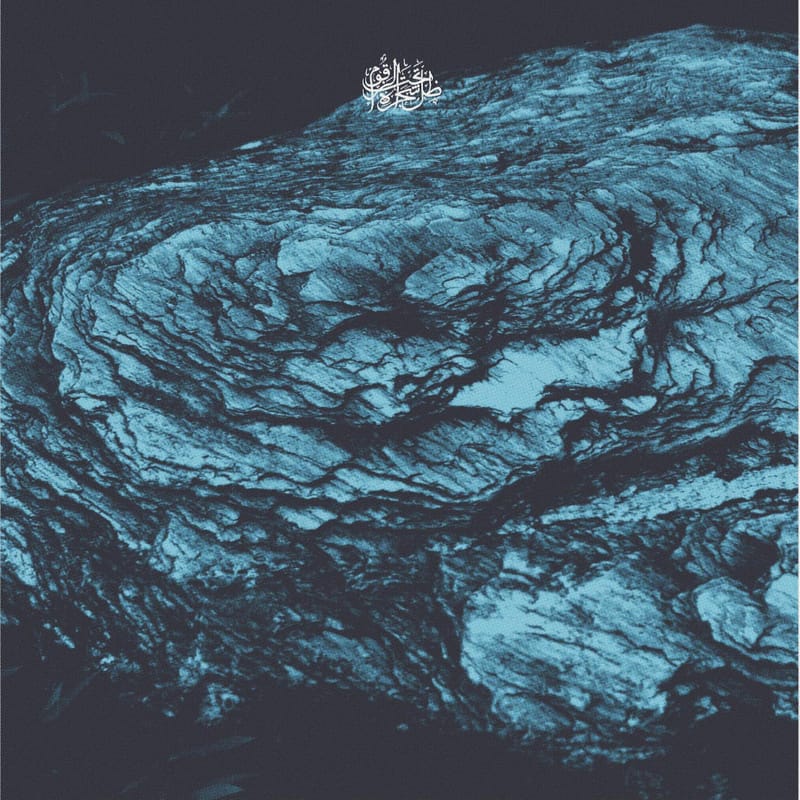

MSYLMA, Dhil-un Taht Shajarat Al-Zaqum

Even if—like me—you need to rely on hearsay and your own sense of good faith to make sense of the narrative on Dhil-un Taht Shajarat Al-Zaqum, the rewards are astonishing. MSYLMA’s voice drips with sadness, anger, despair and hope, each line delivered in a wash of reverb and echo to make matters all the more otherworldly. To delve into Dhil-un Taht Shajarat Al-Zaqum is to submerge oneself into a dream world, drifting along or swallowed whole by Myslma’s bold combination of ragged electronics, subtle melodies and impassioned delivery. On “Li-Kul-i Murad-in Hijaa,” this explodes into a cosmic vortex as free-form drums, crackling guitar and buzzing bass all collide like a hurricane sweeping down on a house. (The Quietus)

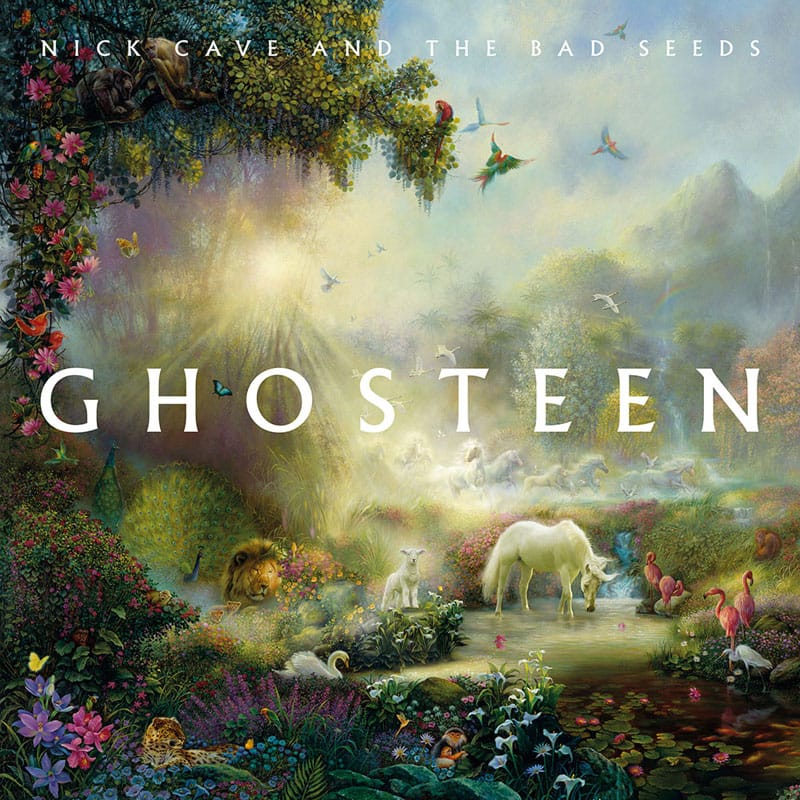

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, Ghosteen

That’s where we find him on Ghosteen, sorting through sensations of despair and persistence. Cave has cryptically said that the songs on Ghosteen’s first half are the children, while the interwoven triptych that follows are their parents. Those final three pieces are discursive and raw, pulling the broad emotional sweep of grief into a series of overstuffed settings. During “Ghosteen,” Cave counterbalances the wonder of being alive at all—broadcast over a sudden surge of strings and the record’s only cavalcade of drums—with the pedestrian cruelty of washing his dead child’s clothes or realizing almost absentmindedly that his family is now smaller. And “Hollywood” begins with seething rage, Cave looking to lash out at anything within reach, to hold even nature itself responsible for his loss while he waits for his own death. In the end, he relays the fable of Kisa, calming his nerves not with the company of others’ misery but with the wisdom that our sadness is but a point on an ancient timeline. (Pitchfork)

Nilüfer Yanya, Miss Universe

The songs on Miss Universe are minimal and instinctual — there’s a shagginess to them, they flow freely. The formlessness of her songs mirror the states of mind they explore, circuitous ideas that worm around with no definitive conclusion. “This is what it feels like/ I’m not sure I feel it,” she sings on “Paradise.” When she hits on an idea that feels like it might unlock a solution, Yanya leans in hard. These tend to be the big moments on Miss Universe, when everything seems like it might suddenly fall into place: on “Baby Blu,” a pulsing dance track about moving on from love, or on “In Your Head,” a dizzyingly catchy one about accepting that you’ll never be able to figure yourself or anyone else out. (Stereogum)

Nivhek, After its own death / Walking in a spiral towards the house

Opening with “Cloudmouth,” its beginnings seem like a Harris hallmark, but then halfway through it becomes the Blade Runner soundtrack almost, with this dense synth that conjures malevolent thoughts, something Harris isn’t shy to elaborate on through the massive soundscapes she’s crafted. All of these songs grouped together to segue seamlessly from feeling to feeling isn’t unheard of, but it works to Harris’ advantage. It forces the listener to engage each individual concept: from the handbells of “Night-walking” to the chimes of “Funeral song” that close out Side A of After its own death, Harris has her grip on us. (Soundblab)

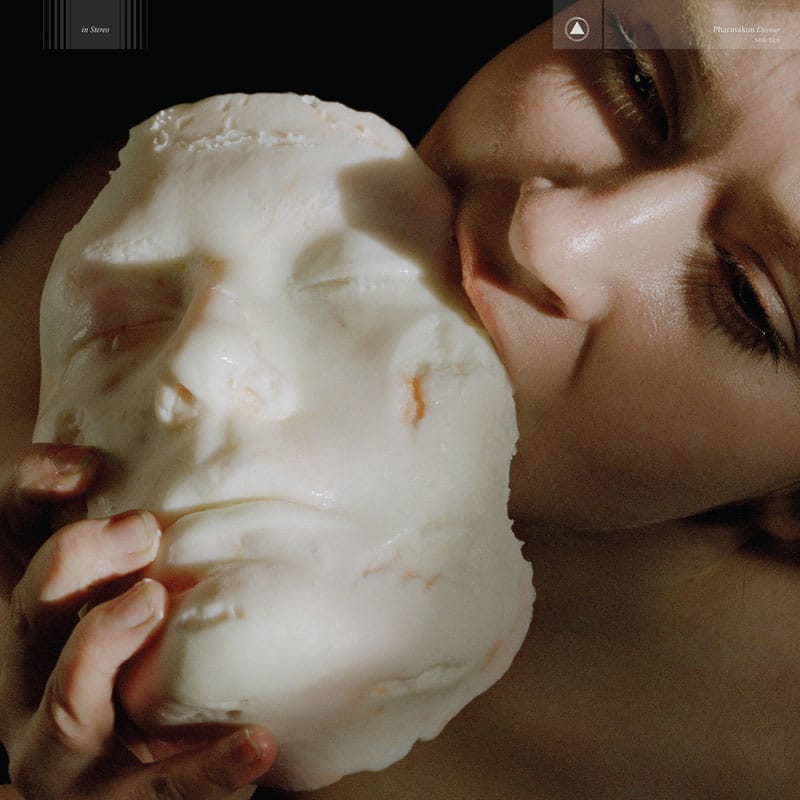

Pharmakon, Devour

Pharmakon’s voice traverses Devour’s textured rhythms and spurting feedback, serving as antagonist and guide. From the modulation and distortion of “Homeostasis” to the delay and low register of “Spit It Out,” to the momentary clarity of “Self-Regulating System” and back to the ricocheting uncertainty of “Deprivation,” Margaret Chardiet’s voice weaves together the noise pricking at the body’s surface and a deeper sense of something coming from inside the body. The voice and the various effects applied to it push and pull against the skin. A sense of unease that is also a sense of knowing again what a body already knows — “an awareness you cannot think or say, only feel,” as stressed on “Pristine Panic.” (Tiny Mix Tapes)

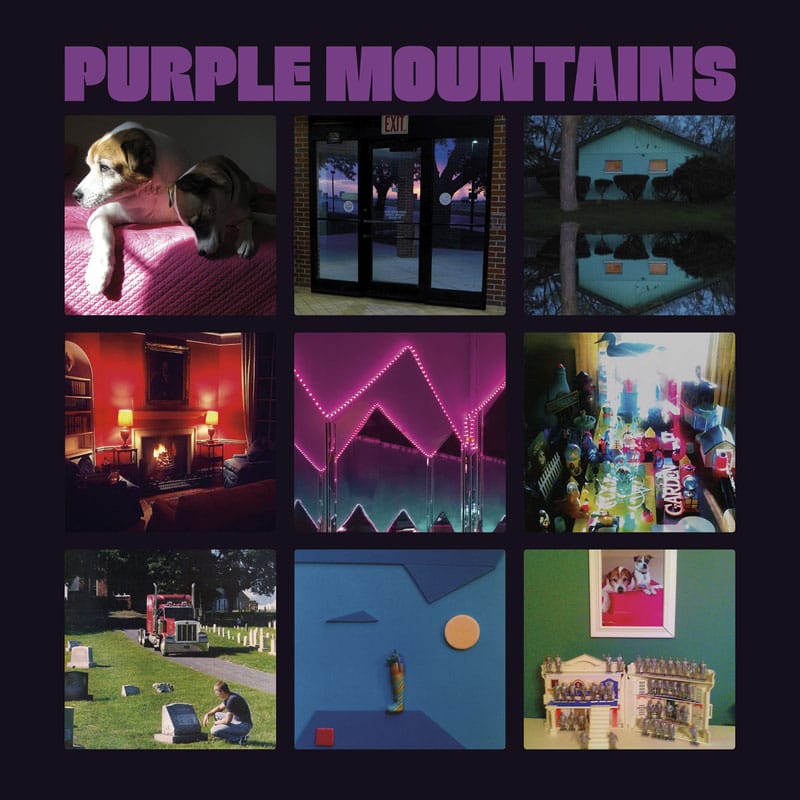

Purple Mountains, Purple Mountains

The way Berman tells it, he picked up a guitar again after his mother’s death. “I think it was like meditation, but it was also like a massage,” he said of that familiar exercise, the wooden body vibrating against his chest. His strumming eventually spiraled into “I Loved Being My Mother’s Son,” a gentle highlight from his new comeback album under the name Purple Mountains. Lyrically bereaved but musically at peace, it sets the tone for the record as a whole. These are plainspoken songs of heartbreak, grief, and bitterness. One ballad, “Nights That Won’t Happen,” can be heard as a pros-and-cons list of just being alive. Backed by members of the Brooklyn psych-folk band Woods, however, Berman’s writing has never sounded so exacting or direct. These songs offer a solid introduction to all the beautiful contradictions that have always made his work so comforting and complex—a rare feat for a comeback album. (Pitchfork)

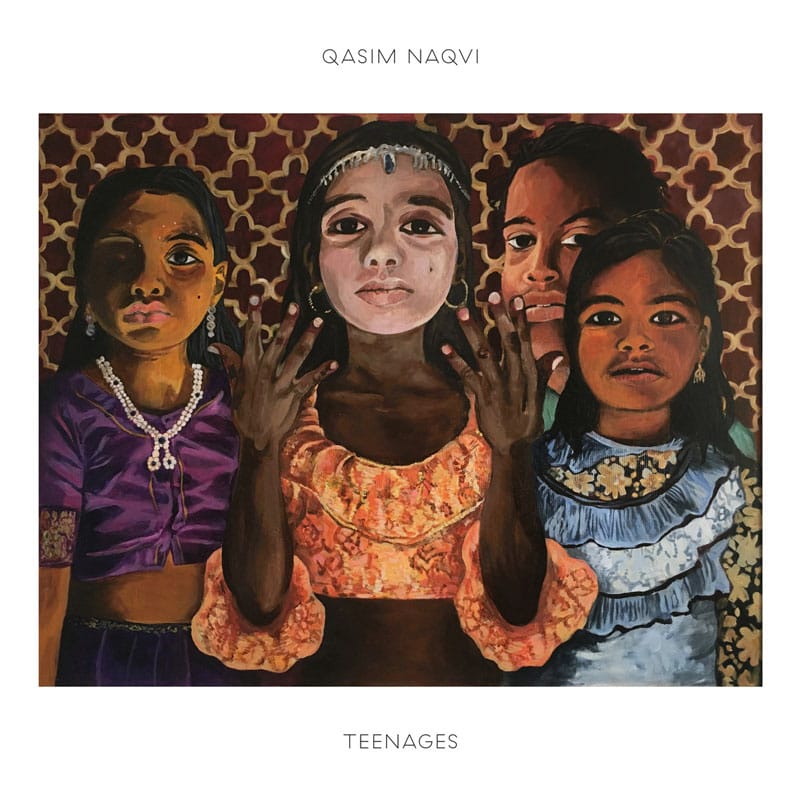

Qasim Naqvi, Teenages

The album’s opening track, “Intermission,” germinates from a darkly planted seed seemingly embedded within a single tone. The harmonic spectrum that emerges ultimately twinkles with crystalline iridescence, like light glinting off the surface of some unknown metal. Similarly, “Mrs 2E,” “Palace Workers,” and the mysteriously entitled “No Tongue” carve paths away from their respectively brooding nuclei and fracture into ear-tickling rhythmic ostinatos overlaid with pulsing tonalities in a glittering, musical mitosis. While some music created with modular (or more precisely, “subtractive”) synthesis results from capturing the incidental fallout of twisting knobs and flicking switches, Naqvi’s works are thoughtfully devised compositions that each emanate a subtly distinct personality and resonate together in the context of the album as a multifaceted whole. They are the movements of a symphony, designed and executed with clear intention. (I Care if You Listen)

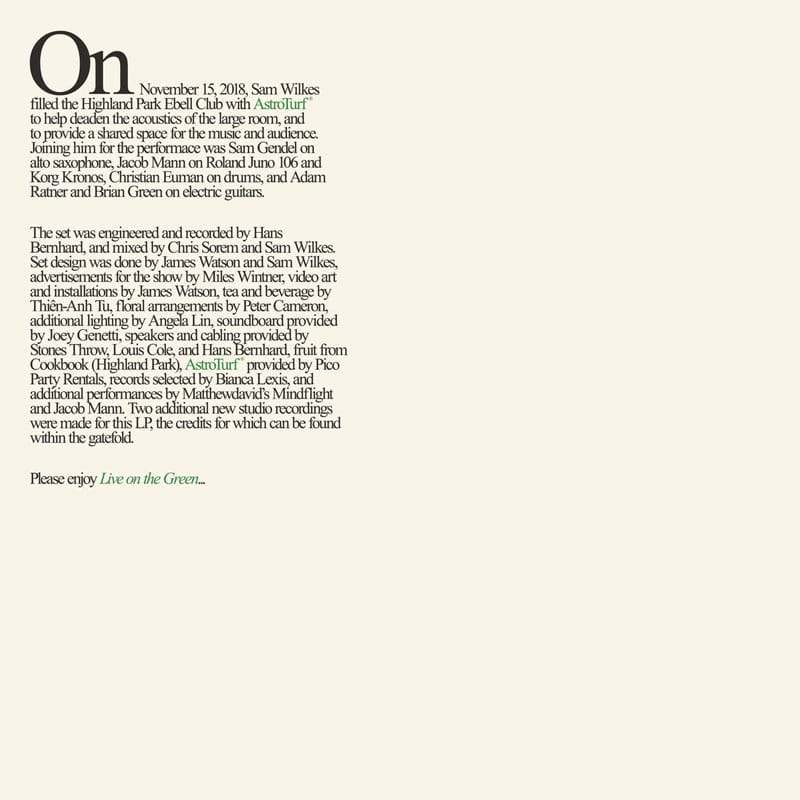

Sam Wilkes, Live on The Green

While it’s an admittedly unorthodox move to follow up your debut with a live album — particularly one that pulls half its tracklist from the debut — Live on the Green nevertheless feels like an artistic expansion for Wilkes. Despite the abundant good vibes, there’s an undercurrent of sadness that runs through these songs that was missing on WILKES. On that album, the gorgeous closer “Descending” felt like a mission statement whispered from one lover to another. On Live on the Green, where its two airy parts surround Alice Coltrane’s “Sivaya” and a new original called “Unsure,” “Descending” feels like a long exhale made bumpy by tears, the end of one thing finding strength in knowing that it’s the beginning of something else. (Aquarium Drunkard)

Sarah Davachi, Pale Bloom

Piano was Davachi’s first instrument, and on “Perfumes I–III,” the three-part suite that makes up Pale Bloom’s A-side, it plays an elemental, if ultimately complex, role. Before eventually returning to the sustained tones that characterize so much of her work, the album first wanders through the field of classical composition. The melody on “Perfumes I” is minor, elegant, affecting but grayscale. More dramatic than the piano notes themselves is the cold silence that punctuates them, lasting for seconds at a time. Midway through, a drone (the piano processed backwards?) begins to pulse its way to the forefront. It intensifies the sound—the piano takes on a slight dynamic insistence as it begins a heartrending ascent into a higher register—and also makes strange our sense of environment. It is as if a window in the room had let in an unsettling breeze from an advancing storm. (Pitchfork)

SAULT, 7

Plundering the past with high-octane abandon, Sault have an incredible sense of which routes lead to the dance. There’s nothing circuitous here, nothing wasted, just an irrepressible desire to find the quickest short-cut to pleasure. Consequently, tracks like “No Bullshit” and “Feels So Good” sound like they were cut in the rush of excitement as soon as the hook had caught. This sense of abandon continues—though taking on a very different form—in “Smile and Go”, which fuses the DIY sound with elements of R&B and African funk. Meanwhile “Threats” is an incredible piece of UK soul—smooth in intent and raw in delivery. It’s about as affecting combination as I’ve ever heard. (The Arts Desk)

Slauson Malone, A Quiet Farwell, Twenty Sixteen to Twenty Eighteen

Above all, it’s an album that rewards close, undistracted listening. Marsalis’ music inspires deep-digging into yourself (or Google) because when you’re lost in a song, replaying it, you pick up on new details each time, and realize every sound has a purpose. Whether the sounds are mournful sirens and screams or a saxophone riff on “(Fred Hampton’s Door Into Farewell Sassy) Na” that makes it feel like you’re the only attendee at a cigar-scented jazz club. (Pitchfork)

Slugabed, any attempt to control the environment or the self by means which are either untested or untestable, such as charms or spells

From the opening salvo, you realise this is the same Slugabed you’ve always known, but there is something different too. He’s decided to be more open and honest with us. The tracks feel slightly unfinished, or at least, a living work in progress. At times you feel like the idea is more important to Slugabed than the finished article and this is incredibly rewarding. It’s like he is peeling away a layer of the creative process and we can see how is mid works. The standout track is “Y U Stuck There,” which features Activia Benz alumni Mr. Yote. As usual Yote is off in Yoteland and even after half a dozen listens, I’m still unsure what he’s going on about, but whatever it is, is brilliant! His flows work perfectly with the music. “Clanggg” is the most cohesive and polished, and reminds us of Slugabed of old. Its inclusion is as if to remind us why we’re here in the first place. (The Ransom Note)

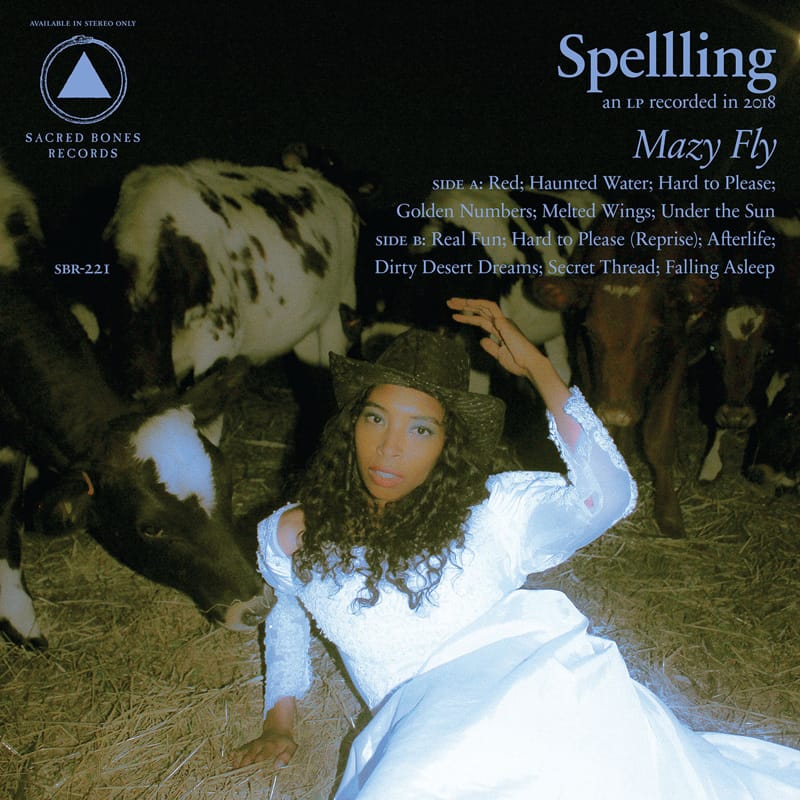

Spellling, Mazy Fly

The absolute second it begins, the track captivates. This glitch-pop-meets-disco type production topped with Cabral’s vocal strength is beyond gorgeous. She cries, “I am your faith, but it’s not enough to build a bridge over haunted water,” elongating almost every syllable, stressing an other-worldly desire that touches on both colonialism and slavery in America’s past; how it still trickles through to modern times. As the song draws to a close the bass becomes more and more prevalent, allowing for a sense of structure within the many different ideas Spellling has played out for us. (Atwood Magazine)

Stephen Vitiello, Taylor Deupree, Fridman Variations

For the 18-minute experimental improvisation on the A side, and the two entirely new works recomposed, comprising of the original live source material on the flip side of the 12″, the duo work the guitar (Vitiello), modular and small tape synths (Deupree) into a drifting meditation of acoustic textures, lo-fi shuffles, and the exploratory interactions thereof. “The improved layers draw on buried melodies and a hint of field recordings and found textures […] not overly melodic, not overly noisy […] finding the edge between the pretty and the obscure…” The archival document of a live performance carries with it a particular moment captured in time, including the presence of the listeners deep in the night, and the surrounding ambience of the venue itself. The variations then build advance on the approach, a bit more polished front and centre in a “controlled studio environment.” (Headphone Commute)

Sumac, Keiji Haino, Even for just the briefest moment / Keep charging this “expiation” / Plug in to making it slightly better

The title track, the longest song on the album at roughly 30-minutes, is an anticipated slow burn. The song eerily crawls, growing naturally in noise and vigor until the group, around 16-minutes in, is fully-flexing and annihilating everything in their path by sheer force. The song then breathes a little, as Haino performs spoken, often screamed, word over the drums, with waving electronics and the drums in the background. The track moves through a few more peaks and valleys of energy before finding its end. The final song “(first half)/Once, twice, thrice/…” is the most brooding of the collection, and also where Haino’s vocals are the most central—musically the song never reaches the same levels of chaos as its predecessors, but Haino’s visceral performance makes up for it in spades. (Post-Trash)

Sunn 0))), Life Metal

Though the album’s joyous moods might raise questions among listeners who don’t typically equate Sunn O))) with such positivity, Anderson describes Life Metal as “very much Sunn O))),” adding “It still sounds very heavy and powerful, but the choices in the tone, Albini’s recording, and some of the choices of arrangements have this brightness and a symphonic quality.” (NPR)

Sunn 0))), Pyroclasts

Pyroclasts is a companion to that album, recorded in the same sessions but stripped even further back. At the start and end of each day of recording, the group and their collaborators would perform a simple exercise: explore a single modal drone for 12 minutes; Albini would capture it, and they would move on. These four selections can be experienced as a sort of frame for Life Metal’s more definitive statement. Not compositions, nor exactly improvisations, the group describes them as “a daily practice,” calling to mind a regular meditation or yoga routine (except at pain-threshold dB). And like a series of stretches, these sessions were intended to open up the musicians as they worked through the album. (Pitchfork)

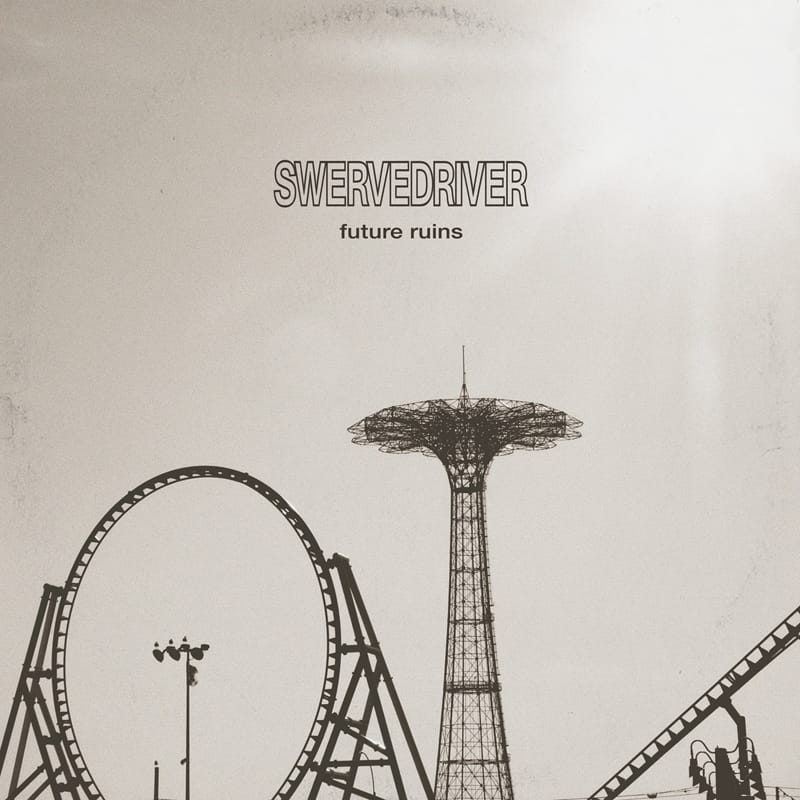

Swervedriver, Future Ruins

Swervedriver have always connected with devoted music heads—Grammy winner and Future Ruins engineer TJ Dougherty first came to the attention of the band years ago when he was a fan in the front row at every show they played in New York—but the potential to reach a wider audience was always there, too. To that end, the instantly hummable “Drone Lover” and “Spiked Flower” of the album’s mid-tempo middle could be a sign that the desire to give the postman something to whistle might finally be catching up with them. Whether or not Future Ruins is the record that finally breaks Swervedriver through to the masses, it shows the band are still making their own breakthroughs. (PopMatters)

The Comet Is Coming, Trust In The Lifeforce Of The Deep Mystery

Take lead single “Summon the Fire” for example, a rowdy 160bpm cut that blends pounding drumlines with appropriately spacey synths. Hutchings’ saxophone carries the melody, squawking through various effects until it reaches a triumphant hook that wouldn’t sound amiss on a Prodigy record. So boisterous is the track’s bridge that at times it threatens to morph into the kind of happy hardcore revivalism that’s dominating the UK’s clubs. If this is jazz, it’s jazz for football hooligans, and it is utterly glorious. (The Quietus)

The Comet Is Coming, The Afterlife

But there’s something in the way the Comet Is Coming skewers the typical jazz trio that stands apart from his other projects. Its surface speaks to the cosmic sounds of Sun Ra, but there’s something raw and earthy at the core. Comet draw from the minimal, restrained palette of the trio format to make something that’s electrifying and apocalyptic all at once, able to tear the roof of jazz—as well as rock, jam band, and EDM—festivals. A companion piece to this year’s Trust in the Lifeforce of the Deep Mystery, The Afterlife continues to hover over that album’s scorched earth, not replicating the rush of “Summon the Fire” but instead exploring in greater detail that set’s most somber moments. It’s concise yet also shows the trio’s depth in just over 30 minutes. (Pitchfork)

The Newcomer, Inner Being

This album helps me feel less alone. (.proxy on Bandcamp)

These New Puritans, Inside The Rose

As These New Puritans evolved into a visionary post-classical pop group, their music became marked by the whisper of war, a bellicose current their first great song made overt. Inside the Rose opener “Infinity Vibraphones” is swept with evil-armada strings and battlefield snares, even as it spills imperceptibly from something adjacent to “Carol of the Bells” into silky vibraphone jazz. On “Into the Fire,” an adrenalized electronic scribble scrambles through a fortress of piano chords pounded by drums. Yet the group render warlike tropes so gently, with such containment and poise, that they seem to dramatize figurative battles of the heart rather than literal ones. (Pitchfork)

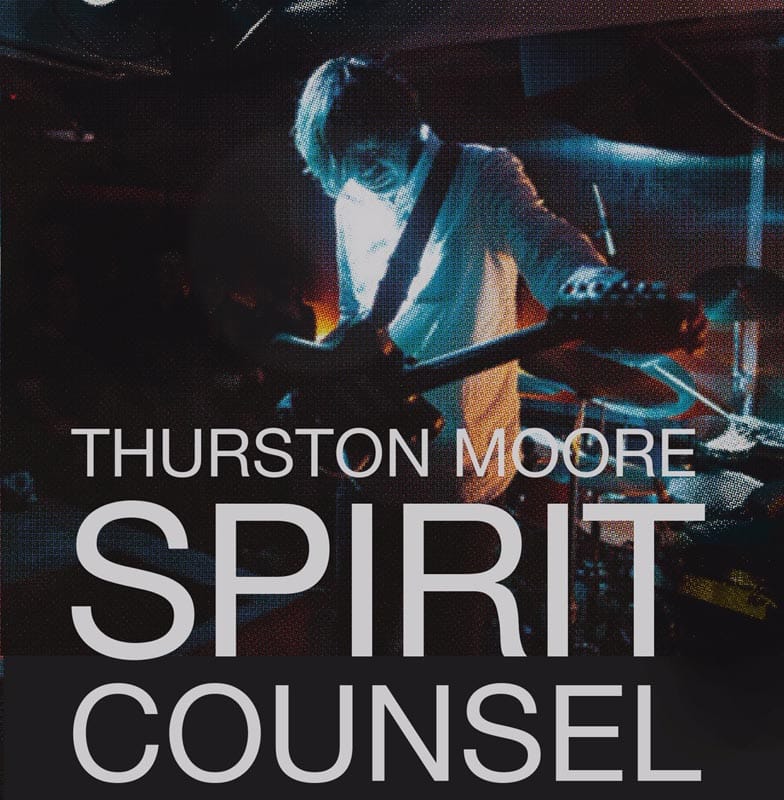

Thurston Moore, Spirit Counsel

Things drop into a gallop with straight-ahead bass/drums and chugging guitars delving through very familiar territory for Moore before the chaos starts to rise to white noise levels around the half-hour mark. This is also comfortable footing as the din dances around speakers before melting into more melodic terrain. The journey is fulfilling and scenic as things never become too far removed from the path, yet remain adventurous, gliding easily towards a swirling rock-inspired climax of pounding low end, digital blasts, feedback and ringing chords. (Glide Magazine)

Tim Hecker, Anoyo

The uchimono drum, the hichiriki and ryūteki flutes, and the 17-piped mouth organ called the shō are not often heard outside Japan, the music having only been opened up to the public in the past century. But while Konoyo used these singular sounds like a chisel, Anoyo paints with wide brushstrokes. In a space between percussive surges of the track “Not alone,” a voice is heard saying something in Japanese, perhaps a comment from in between takes. To keep it sounds like an intentional mistake, oxymoronic as it is, and a step away from obsessively obscuring the authorship of sound, just letting it be what it is. (Resident Advisor)

Tony Njoku, Your Psyche’s Rainbow Panorama

Whether in the violent grinding synths of “FURIOUS,” the glitchy, detached emotive quality of “DISCONNECTED” or the abrasive arrangement juxtaposed with Njoku’s falsetto in “GLORIOUS,” there is a sense of brave experimentation, where each individual track telling its own story and highlighting one specific emotion—as the title of each track denotes- within the jumble of vocals and psychedelic electronic sonics. (Clash Music)

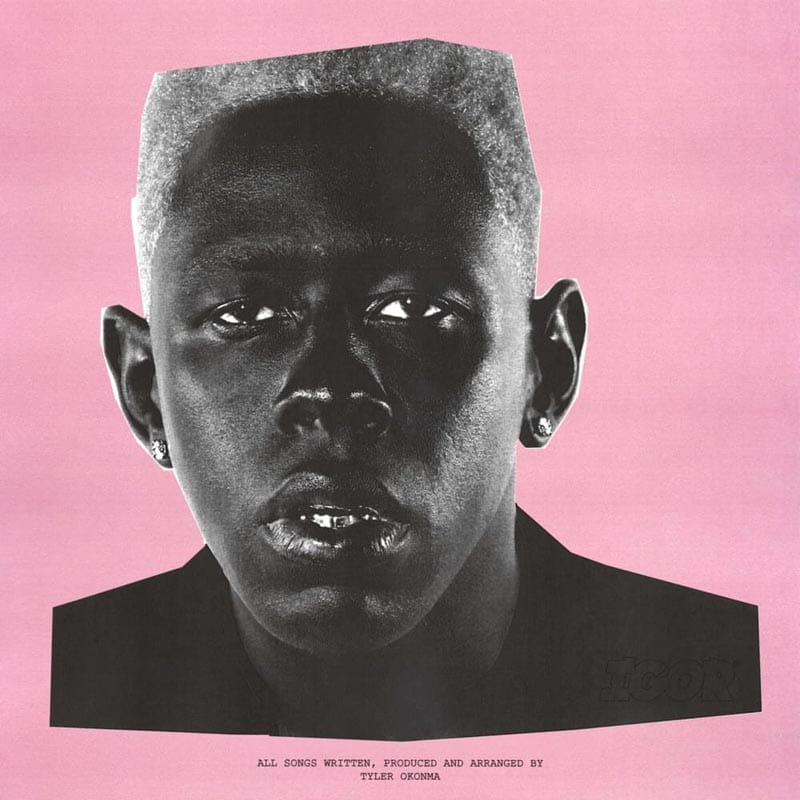

Tyler, the Creator, IGOR

IGOR sounds like the work of a perfectionist giving shape to his more radical ideas. Tyler, who proudly produced, wrote, and arranged the album, is singing more but he’s not worrying whether his tracks have a traditional pop arc. Songs don’t build to a crescendo, they often begin there. The opening “IGOR’S THEME” serves less as a guiding force and more like a recurring motif of doom that hides in the shadows and pops its head in at select moments, like on “NEW MAGIC WAND” where spooky synths erupt below Tyler’s thought process: “I saw a photo, you looked joyous,” goes one of the more poignant lines. Atop this budding dread, Tyler layers candied keys and harmonizing vocals. The brightness is defiant, as Tyler processes the loss of someone he loves. (Pitchfork)

Uniform, The Body, Everything That Dies Someday Comes Back

The first track slowly unfolds with distorted, rhythmic patterns until the bands’ collective clutches start to reach out for you and drag you downwards. The following two tracks have a more constant pulse and drive to them, but it’s the fourth track, “Patron Saint of Regret”, that really grabbed me and emerged above the earlier tracks. The haunting choir swells, female vocals, deranged and a bit out of tune guitar leads, and the overwhelming atmosphere altogether make this track the most noteworthy individual piece of this album. Possibly even the most noteworthy individual track released this year altogether, actually. (Everything Is Noise)

Visible Cloaks, Yoshio Ojima, Satsuki Shibano, FRKWYS Vol. 15: serenitatem

The natural world is never far away on serenitatem. Faint animal noises are heard in the background of “Atelier.” Something like a gurgling stream appears in “Lapis Lazuli.” But it’s the digital textures that dominate. Visible Cloaks’ trademark MIDI-esque vocals are scattered throughout, albeit sung by Shibano herself. The melodies were created by feeding text written by Ojima and Shibano into the generative music program Wotja. Despite the use of such technology to create serenitatem’s immaculate soundscapes, the album’s most affecting piece is its most traditional, a rework of the French medieval song “S’Amours Ne Fait Par Sa Grace Adoucir (Ballade 1).” The collaborators embellish the original’s lilting organ-like melody with watery sounds and gleaming synths, transforming it into a beautiful, winding electroacoustic lullaby. (Resident Advisor)

Vivian Girls, Memory

Sitting just below thousands of guitars, the vocals provide numerous pleasures, despite rarely coming into full view. Ramone spins deadpan tales of relationship hell and terminal self-loathing with sullen authority as Goodman and Kohler add high, lonesome harmonies to sweeten these grim testimonials. (Consequence of Sound)

William Basinski, On Time Out of Time

The 39-minute composition may draw from deep in the universe, but it retains the telltale intimacy of all Basinski’s work. There are spectral drones, the warm crackle of static, the squiggle of radio frequencies in the night air. “It was just coming from the sky,” Basinski used to say of his culling method, one hand on the dial of his shortwave radio. As much as the use of space recordings is aligned with Basinski’s method, it also harks back to his own childhood, growing up in Houston, where his father worked for NASA in the early 1970s. (Pitchfork)

Yann Tiersen, All

It’s as ambitious an album as one entitled ALL should be. That’s not to allude to any particular complexity or grandeur, though it contains both in high and equal measure, but in what the French composer tries to achieve conceptually and as a sonic experience. As its depths unfold it’s clear that with ALL, Tiersen is trying to encapsulate all that it means to be human, to exist with each other in and as part of the natural earth and further into the cosmos. All means all, and the result is an album of joyous, yearning beauty. (Drowned in Sound)

Yann Tiersen, Portrait

In Yann Tiersen’s own inimitable way, he has with Portrait reimagined the concept of a “best of” album. He has taken on the massive task of reviewing his legacy to date by taking a completely analogue based approach to re-recording 25 songs from across his extensive career, the result of which is a completely engaging and rather brilliant album which serves both as introduction to and compilation of some of the great Breton’s best works. (musicOMH)

Originally published at The Morning News